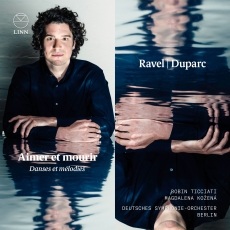

Robin Ticciati & DSO - Ravel & Duparc: Aimer et mourir - Fanfare (MV)

Robin Ticciati takes Ravel at his word and interprets Daphnis et Chloé Suite No.2 as a “choreographic symphony” rather than simple dance music. The dual implications of the composer’s description shine through each ray of the opening daybreak and beyond as a glowing and limpidly recorded account unfolds, awash with colors and rich in balletic grace and musical complexity. Impish, precise flutes skip through the central pantomime before giving way to a Russian-flavored chase. It evokes Rimsky-Korsakov, but may well have been intended as a homage to Diaghilev, the impresario who commissioned it. This is an exquisite account of a familiar score, sumptuously recorded and impeccably played by the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin. Ticciati’s meticulous attention to matters of tempo, dynamics, and internal balance result in music-making that’s as ravishing as it is idiomatic.

Afterwards, though, something strange occurs. Gears grind and spritely Ravel gives way to soupy Duparc as Magdalena Kožena joins the orchestra, and between them the Czech mezzo-soprano and the young English conductor give readings of four much-loved songs that are indulgently slow and self-absorbed. Right from the oscillating semiquavers that usher in L’invitation au voyage there’s a Hollywood plushness to these readings, as though Baudelaire’s allusion to “luxe, calme et volupté” is all that matters. Yet Duparc was a controlled Romantic and Kožena’s slinky crooning misrepresents both him and, at times, the French language that she normally pronounces so well. She leans into “Les soleils mouillés / De ces ciels brouillés” (The misty suns / of those changeable skies) as though draped over a grand piano, while elsewhere she elongates individual words (“vagabonde,” “revêtent”) in sultry but unidiomatic ways. It’s a puzzle, not least as the mezzo’s recent account of Debussy’s Mélisande was so persuasive. The plangent melancholy of Au pays où se fait la guerre (To the country where war is waged) is given a desultory reading and Gautier’s heart-rending text goes for nothing. The composer’s Chanson triste (Sorrowful song) fares no better, because without the inherent sadness it becomes a lullaby. Of the four melodies only Phidylé fares well, perhaps unsurprisingly given that it is Duparc’s most nakedly romantic song.

The lurch out from Duparc’s corner is happier than the lurch in, as Ravel returns with music of elegance and wit. The buoyant Valses nobles et sentimentales have common ground with Duparc’s songs in that they derive from piano originals. Ticciati’s performance here is a joy: He navigates the music’s syncopations and dynamic shifts with easy assurance, and the penultimate moins vif is rendered almost cheeky in its Viennese allusions. Duparc’s five-minute Aux étoiles for orchestra makes an imaginative coda to the disc, as well as intensifying an abiding regret that he produced no music at all during the last half-century of his life.