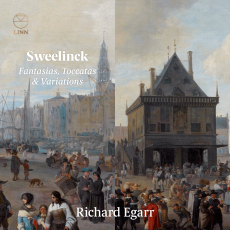

Richard Egarr - Sweelinck: Fantasias, Toccatas & Variations - Gramophone

Despite his enormous influence on Dutch and north German music, especially the composers Bach would study in his youth, Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck has a precarious hold on the repertoire. Harpsichordists will occasionally play one of his fantasias or toccatas, and his variations on secular songs and dance melodies make more frequent interstitial appearances on concert programmes. But a whole programme of Sweelinck, a Dutch composer born in 1562, is a rarity.

Richard Egarr, who devotes his most recent disc to 11 of the composer’s most appealing keyboard works, explains why: ‘Sweelinck’s music has suffered from many objective, colourless and academic performances and recordings in the name of “authenticity”.’ Without naming names, it’s fair to say that Egarr is right, though Sweelinck presents uncommon challenges to contemporary performers and listeners alike. Even more than the English virginalists, with whom he was contemporary, Sweelinck delights in music that divides and subdivides thematic material, building up intensity through accretion of fast-moving variants on the basic line that, if rendered pedantically, inevitably sound both cluttered and ponderous at the same time.

This is a fundamental misinterpretation of what the music is about, says Egarr. In the booklet, he quotes a rare first-hand account of an evening spent with Sweelinck at the harpsichord, when he was in ‘a very sweet humour’ and played for hours for his guests. Sweelinck, avers Egarr, was Dutch and thus his ‘world was hugely colourful, full of many international influences and religious diversity (all of which were tolerated in the name of commerce) and he provided music which brilliantly reflects this’.

Egarr doesn’t stack the decks for his argument by limiting himself to the handful of Sweelinck works that might be deemed popular today. He includes the Paduana lachrimae and the variations on Mein junges Leben hat ein Endt, which are among the better-known of the composer’s works. But he renders Mein junges Leben in a style almost more austere (and with flowing, even brisk tempo) than he uses for the supposedly more abstract fantasias and toccatas. And yet both are effective and appealing.

In the fantasias and toccatas, he allows air in between episodes, letting the music pause and relax before the division of material begins again. And that division is never strictly mathematical. Faster-moving music will sometimes pass by as a flourish and sometimes inflate and stretch the musical arc expressively. He deploys ornamentation effectively, and sometimes breaks or rolls a chord figure to clarify where one line ends and another begins.

About midway through the Fantasia crommatica, the tenor and bass lines begin another meditation on the half-step descending line, and Egarr allows this to function a bit like the slow movement in a sonata, a chapter of placid intimacy and meditation. The chromatic ground is now distended to semibreves, the tenor responds in crotchets and a few lines later the engine is purring along again, leading to semiquaver figuration and then rapid triplet figures. But the ear doesn’t notice these ratios, only an increase in urgency and colour. Egarr’s particularly piquant quarter-comma meantone tuning adds a frequent dash of lemon and lime to the mix. He hopes, he says, ‘to persuade you the listener of the glorious nature of this rich and wonderful music’. Mission accomplished.