Arcangelo - Handel Brockes-Passion - Gramophone

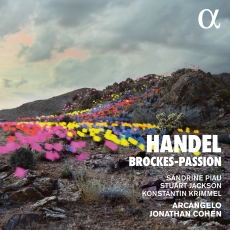

If Bach’s Brandenburgs reveal the Lutheran Kantor at his most robustly Handelian, the tables are turned in Handel’s sole Passion setting, many of whose numbers could, on a blind taste, be mistaken for Bach. After unfairly languishing at the margins, the Brockes Passion finally came into its own with no fewer than three recordings in 2019, the 300th anniversary of its first known performance. This new studio recording from Jonathan Cohen’s Arcangelo might seem unlucky in its timing. Had it appeared two years ago it would have swept the field. Today it faces serious competition from the Academy of Ancient Music and Concerto Copenhagen. That said, it easily holds its own. Using just 10 strings and a consort of eight singers, Cohen presents a performance on a chamber scale. Yet the crack players of Arcangelo yield to none in colour and dramatic tension. The drama is animated by an imaginatively varied continuo of lutes, chamber organ and harpsichord. And the soloists are uniformly fine.

A crucial factor in a performance of the Brockes Passion is the casting of the Daughter of Zion, whose 14 arias range from the elegiac ‘Brich, mein Herz’ and the sublime soprano-oboe duet ‘Die ihr Gottes Gnad’ versäumet’ to the furious protest of ‘Schäumest du, du Schaum der Welt’. I find it impossible to choose between Elizabeth Watts, for Egarr, and Cohen’s Sandrine Piau, both of whom sing beautifully and ‘live’ their music intensely. If Watts has a purer tone and a more elegant style, Piau, with a dark flame in her lyric soprano, risks more. She throws herself with barely contained delirium into ‘Schäumest du, du Schaum der Welt’ and the following ‘Heil der Welt’, whose opening Handel pilfered for the Concerto grosso Op 6 No 1 – one of so many instances of Handelian recycling in the Passion.

With a more heroic timbre than Egarr’s Robert Murray, Stuart Jackson wrings every drop of drama and pathos from the Evangelist’s narrative: arguably too much so in his long-drawn-out recitatives towards the end, which flow more naturally from Murray. But Jackson always makes you listen. Konstantin Krimmel, though lacking Cody Quattlebaum’s bass depth, is both sympathetic and, where apt, fiercely incisive as Jesus. The keening duet between Jesus and Mary Bevan’s anguished Mary is a musical highlight. Mhairi Lawson’s shining soprano excels in her reflective arias towards the end of the work (the assuaging ‘Was Wunder, dass der Sonnen Pracht’, softly coloured by bassoons, is one of several foretastes of Acis and Galatea), while Matthew Long’s agonised Peter is every bit a match for Gwilym Bowen on the AAM recording – high praise indeed. The luxuriously produced, lavishly documented AAM recording, urgently directed by Richard Egarr (his tempos almost invariably a notch or two faster than Cohen’s), will remain a top choice for many. But no Handel lover should regard Arcangelo’s more intimate performance, meticulously prepared and superbly executed, as second best. Fans of Sandrine Piau, of course, will need no prompting.