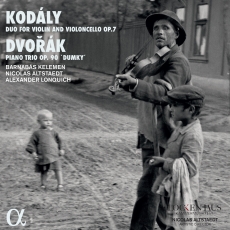

Barnabás Kelemen, Nicolas Altstaedt & Alexander Lonquich - Kodály: Duo for Violin and Violoncello, Op. 7 - Dvořák: Piano Trio, Op. 90 "Dumky" - Presto Classical

Back in August 2019, I was blown away by a superb recording of Bartók’s rarely-heard early Piano Quintet and Sándor Veress’s equally underexposed String Trio from the Lockenhaus Festival on Alpha Classics; the album went on to bag the Chamber prizes at both the Gramophone and BBC Music Magazine Awards the following year, thanks not only to the relatively unusual repertoire but also the total synergy of the ensemble and the incredible range of colours which they conjure together. The line-up included violinist Barnabás Kelemen, pianist Alexander Lonquich and cellist Nicolas Altstaedt (who succeeded Gidon Kremer as Artistic Director at Lockenhaus in 2012), and on today’s Recording of the Week the three reunite for another illuminating pair of works from Central Europe – Dvořák’s much-loved Dumky Trio from 1891 and Kodály’s Duo for violin and cello from 1914, both of which draw inspiration from the folk-music of the composers’ homelands.

It’s certainly a sequel to be reckoned with: barely a minute into the Kodály (which opens the album in a blaze of gritty glory) I had my suspicions that Kelemen and Altstaedt would be well advised to make space on their mantelpieces come next awards season. The first chord practically leaps out of the speakers, the audible impact of bows landing on strings setting the tone for an account which sees both players utilising the percussive qualities of their instruments to such an extent that there are moments where they sound like an entire ensemble rather than just two musicians – not only do the pair summon a depth and breadth of tone equal to that of a whole string-section in long stretches of the first movement, but they also make full use of the expressive potential of special effects such as strings snapping against fingerboards in the many pizzicato passages.

Like his contemporary Bartók (whose violin concertos fellow Hungarian Kelemen recorded to great acclaim a decade ago), Kodály was fascinated by Hungarian folk-music, and the pair lean into this aspect of the piece with gusto, emulating the sonorities of the zither with their left-hand pizzicatos and the hurdy-gurdy in the drone-like writing which features in the outer movements. Kelemen is also utterly beguiling in the lovely opening of the finale, where the pentatonic ascending melody seems to prefigure Vaughan Williams’s Lark (which was completed in the same year but wouldn’t soar in public for another six years) – indeed the pair’s handling of ascending lines in general is one of the recording’s joys, whether tossing phrases joyously into the air or allowing them to spiral upwards and apparently evaporate. It helps that the blend between Altstaedt’s upper register and Kelemen’s lower reaches is so seamless that in places it’s near-impossible to discern when the music has passed from one pair of hands to the other; for all the thrilling ‘two-man band’ expansiveness in the more exuberant passages, for much of the time the pair sound like a single player in control of some mighty hybrid stringed instrument, with portamenti and chordal writing synchronised to perfection throughout without ever sounding micro-managed.

Such is the synergy between the two players in the Kodály that it’s quite a shock when a third (or, so it seems, a second) party enters the equation in the opening phrases of the Dvořák – not that there’s anything the least bit obtrusive or aggressive about Lonquich’s playing, but Kelemen and Altstaedt’s strings-only sound-world is so complete and compelling that for 23 minutes I’d forgotten that pianos existed! It quickly becomes apparent, though, that he’s just as attuned to his partners as they are to one another: his beautiful handling of the long lines in the second dumka has an almost violinistic quality of its own, and just as his colleagues imitated other instruments with aplomb in the Duo his keyboard seems to morph from celeste to lived-in tavern-piano in the space of a mere phrase. And the lightning shifts in mood as well as timbre are brilliantly captured by all three: rapid switches from melancholy to boisterousness are hard-wired into the piece and the dumka tradition which inspired it, and Kelemen, Altstaedt and Lonquich can flip from one to the other in the blink of an eye.