Mozart Symphonies - SCO & Sir Charles Mackerras - ClassicalSource.com

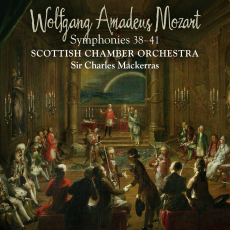

We know that Mozart was a committed Freemason and in his opera "Die Zauberflöte" (The Magic Flute) he is open about it, the plot being very much a Masonic allegory. Its direct Masonic references would certainly have surprised contemporary audiences and would have been thought daring at the time. This comes to mind because of the outer and inner inlay cards and the booklet cover accompanying this release, which feature an exceptionally fine painting of a Masonic Lodge. A blindfolded candidate is being presented with regalia on display; members of the Lodge stand with drawn swords and Mozart sits on a bench on the edge of the proceedings. His likeness here is very close to that of contemporary portraits and it can safely be assumed that it represents the composer. Mozart's enthusiasm for the craft of Freemasonry apart, however, it is difficult to understand the reason for the allusion but the quality of the colour-printing and the presentation are a credit to Linn. So too the recorded quality, which is admirably clear in all departments of the orchestra yet never oppressively forward. This is very much the sound that I have heard when attending concerts under Sir Charles Mackerras's direction.

The ‘Prague' Symphony is given an exceptionally perceptive interpretation, but first the use of repeats is worth describing. In general, sensible obedience to repeat markings is a strong point in this conductor's interpretations: for example both repeats are made in all finales. This is excellent and clearly Sir Charles agrees with Sir Adrian Boult who felt that performances that did not include these repeats would make these ‘late' symphonies, in his delightful phrase, "something of a tadpole". In the ‘Prague' Symphony, I have never seen a score requiring a second repeat in the first movement (but I have no doubt that there is one). Mackerras takes this repeat making the movement as performed longer than the extensive first movement of Beethoven's ‘Eroica'. However, inclusion of that second repeat seems to hamper the symmetry of the work because only the first part of the succeeding Andante is repeated. I thought Mackerras must be unique in choosing this pattern but I turned to John Eliot Gardiner's superb version of two decades ago, I found that he takes exactly the same view and that there are also notable similarities between the two conductors. True, Gardiner uses period instruments at a slightly lower pitch but his intuitive feeling for balance and his strong, one might almost say Beethovenian, approach is very similar to Mackerras whose ‘modern' instruments convincingly approximate to 18th-century timbres with bright woodwind and clear-cut timpani. In both recordings the onslaught of these instruments at the start of the finale's development is beautifully judged.

The similarity between the two conductors is retained in Symphony 39 (also Gardiner's coupling) but Mackerras is a touch faster. He makes the introduction forcefully dramatic and keeps the tempo of the Allegro flowing firmly throughout the movement. The Andante is not allowed to linger and the Minuet is taken at a sturdy Allegretto, sweeping strongly through the Trio, although some might have wished to hear the second clarinet's delightful bubbling accompaniment more clearly. Incidentally, as in all the minuets, Mackerras takes both repeats after the Trio. The finale benefits from brisk speed and dynamic changes. So often this movement can simply run on cheerfully, but Mackerras retains the sense of drama built up in the previous movements.

The second CD does not entirely achieve the admirable conviction of the first. Mackerras uses Mozart's Revised Version of No.40. My view is slightly coloured by the feeling that every performance I hear using the revision, with its additional clarinets, makes me even more firmly convinced that Mozart should have left the scoring as it was. Barenboim, Beecham, Furtwängler, Eugen Jochum and Marriner, come to mind as those who perform the original and all their readings have something special to say. Further, this Scottish performance of No.40 is somewhat understated. The recording seems slightly more general and the strings do not seem to be sufficiently ‘present' to create the essential sense of urgency in the opening movement. The Molto allegro indication (Allegro molto in some scores) is obeyed well enough but the smoothing effect of the added clarinets and the reserved approach to dynamics leaves a pleasing rather than a dramatic impression. The slow movement moves broadly but with ease and Mackerras observes both repeats, which means that the Andante takes twice as long as its predecessor. The Minuet is controversial - Furtwängler set the standard for this movement 60 years ago by his tense forcefulness and his absolutely strict tempo. The Scottish Chamber Orchestra seems to be playing in a light one-in-a-bar at a tempo arguably much faster than the Allegretto marking implies. Sadly the Trio does not keep up the pace so the last hope of dramatic impact is lost. To slow the pace for this section is particularly disturbing, as is the push-forward at the Minuet's return. In Mackerras's 1976 recording of this work, with the London Philharmonic for Classics for Pleasure, this movement was taken at an unchanged moderate pace. The finale improves matters considerably although it is still not the most dramatic of performances.

The ‘Jupiter' Symphony is another matter. A majestic first movement (including a surprising but effective brief slowing before the first fermata) is followed by an Andante cantabile that flows so elegantly that the slowish tempo is amply justified. The Minuet again raises eyebrows, another ‘fast' Allegretto, which gives a waltz-like lilt to the rhythm. The saving grace is that the Trio stays ‘in tempo' - although a little more from the syncopated horn and trumpet fanfares in the second part of the section would have underlined this urgent feeling even more. In the finale, Mackerras is powerful and dramatic - there is great strength and drive here. The entry into the coda is a gripping moment and the commanding weight of the final pages makes for exciting listening.

I am surprised that when I hear Mackerras recordings the matter of da capo observation keeps cropping up. I find these SCO/Linn versions especially interesting in the light of Mackerras's recordings of several Mozart symphonies from 30 years ago with the LPO. At that time I wrote an adverse criticism of the ‘Jupiter' performance because of the conductor's omission of all repeats in all movements except the Minuet, omissions necessary to fit the symphony onto an LP side. I am therefore delighted to hear the current recording confirming his true realisation of the contours of the music.

Despite my reservations about the G minor Symphony, this new set has a great deal to recommend it and the recording falls most graciously on the ear. The chosen venue has an ideal amount of natural resonance, although in Symphony 40 the orchestra seems slightly less forward, but perhaps there are those who, unlike me, do not crave excitement and tension in this work.