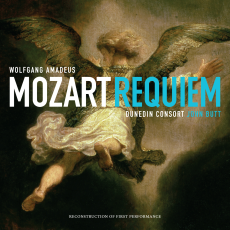

Dunedin Consort - Mozart: Requiem - musica Dei donum

Mozart's Requiem in d minor is one of the most

frequently-performed compositions in music history. It is also the subject of

much debate and research as the composer left it unfinished when he died in

December 1791. Setting aside the myths which have been woven around this work

and the reasons Mozart wrote it, it is especially the way his pupil Süßmayr

finished the score which has been a matter of debate. Most scholars and

interpreters feel that his contributions are rather below the standard of

Mozart's own work, and several attempts have been made to create alternatives

for the parts Mozart did not compose himself. Some 'reconstructions' are quite

radical, others are more moderate, dependent on the view of Süßmayr's work. One

of the aspects about which scholars have different views is to what extent

Süßmayr's completion is based on material from Mozart's pen.

There

has been a time that many performances were based on one of these

reconstructions, for instance by Franz Beyer, Richard Maunder or Robert Levin.

However, I have the impression that today most performers seem to return to

Süßmayr. After all, the reconstructions are all from our time, and Süßmayr is

probably as close to Mozart as we can get. From a historical perspective the

recordings by John Butt and Stephen Cleobury are particularly interesting. Both

perform the Requiem in the edition by Süßmayr. Butt

attempts to reconstruct the first performance in 1793, after Süßmayr had added

the missing parts. His performance is based on a new edition of his version by

David Ian Black who removed some later 'improvements'. Even more interesting is

the line-up of this performance.

The

performance in 1793 was part of a benefit concert for Mozart's widow,

Constanze, which was organized by his long-time patron, Baron Gottfied van

Swieten. The performance was given by the Gesellschaft der Associierten

Cavaliere, which in previous years had also been responsible for the

performances of Mozart's arrangements of vocal works by Handel. Therefore Butt

assumes that the forces with which they performed the Requiem were

about the same as those in these Handel arrangements. He opted for a choir of

sixteen voices, four of which sing the solo parts. This results in a strong

coherence between soli and tutti. Butt states that this kind of line-up was common

practice in the 17th and 18th centuries. Setting aside the number of singers

involved it is certainly true that sacred music was usually not scored for

soloists, choir and orchestra, but rather for a vocal and instrumental

ensemble. There is not only a unity between soli and tutti, but also between

the soloists. That comes especially to the fore in the 'Tuba mirum', but less

so in the Benedictus, due to the slight vibrato of Rowan Hellier. There is also

some vibrato now and then in the tutti, especially in the Kyrie. However, these

are only minor blots on a generally very impressive performance which has

certainly some dramatic traits, but - thanks to the relatively small forces -

is rather intimate, which suits this piece quite well. Butt believes that there

was probably no organ at the performance of 1793 and therefore makes use of a

fortepiano. Unfortunately it is hardly audible.

Butt

also refers to a performance just five days after Mozart's death. It is not

possible to know exactly which parts were performed, but certainly not the

version by Süßmayr as he had not completed the missing parts yet. Butt performs

only the Requiem aeternam and the Kyrie, in a line-up which is probably

identical with that of the 1791 performance: four voices for the solo parts

with four ripieno singers, single strings and lesser

wind. From that time also dates Misericordias Domini (KV 222) which

is performed here with the same forces.

...

John Butt is the only of the four conductors who

opted for the German pornunciation of Latin. That seems historically correct,

and I wonder whether any of the other coductors has given this subject any

thought.