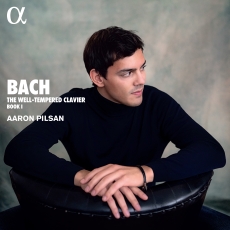

Aaron Pilsan - Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I - Audio Video Club of Atlanta

Twenty-five year old Austrian pianist Aaron Pilsan gives the most memorable account of Johann Sebastian Bach‟s Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I, that I can recall hearing in some time. Like so many of today‟s young lions of the keyboard, he is inclined to regard these 24 Preludes, each followed by a fugue in the same key, as real music and not just exemplars of music theory (which they also are). In this endeavor, he is aided by his tools which include one of the smoothest legatos you are ever likely to hear. That makes it easier to follow the connections and relationships between keys. That is a plus for listeners who are not students of music theory but can recognize a series of beautiful, well-connected pieces when they hear it. Question: Why did Bach call this work The Well- Tempered Clavier? The answer requires a discussion of the difference between “well” (or good) temperament and “equal” temperament. In the latter method, which is commonly used by piano tuners of the present day, the octave is divided into twelve parts, called “semitones.” This allows for an ostensibly seamless flow of chord changes, but it comes with a price. As difficult as it may be for many people to hear, the major thirds are out of tune by just a fraction of a semitone. The result is a compromise that can sometimes sound bland and colorless to informed classical music listeners In Bach‟s well-tempered (wohltemperierte) system, on the other hand, the intervals of the third and the fifth are still slightly out of tune, but the timbre, the basic sound of the different keys, is more pronounced. The music seems to have acquired more character. Of greater significance for performers, Bach‟s method of tempering allowed them to play in all keys without producting noticeably outof-tune inervals. What implication did this have for the future history of the piano? It was immense. For the first time, it provided a viable method of tuning the instrument that would in time allow it to eclipse the harpsichord and other keyboard instruments as the tool of choice for composers as they built up a most impressive repertoire for it over the past two and a half centuries. From the sunny, serenely flowing beauty of the Prelude in C Major, BWV 846 to the profoundly moving Fugue in B Minor, BWV 869 with all its weighty contrapuntal muscle, the emotional range of the 24 preludes and 24 fugues is truly impressive. That is a very personal matter for Aaron Pilsan. “Ever since I became interested in Bach‟s music,” he writes, “ I have never ceased to ask myself how to make the modern grand piano – which has a rich fundamental sound but a reduced volume of harmonics compared to the harpsichord – produce an essentially „well-tempered‟ impression on the listener. But for me it was not a question of instrumental history, but of interpretation.” Of interest is the fact that the final Fugue in B Minor contains all twelve semitones of the chromatic scale. Does this mean that Bach anticipated Arnold Schoenberg‟s twelve-tone system as the basis of composition by a century and a half? You betcha! The implications were there, but composers were slow in realizing them fully. For many years, they contented themselves with the eight major and seven minor keys that were customarily employed until fairly recent times: C-c-D-d-Eb-E-e-F-f-G-g-A-a-Bb-b. In the meantime, adventuresome spirits from Schumann to Scriabin experimented with the expressive possibilities of such relatively exotic keys as C-sharp Minor and F-sharp Minor, both of which Bach employs with great effect in WTC, Book I. And speaking of keys, why does Bach nestle the Fugue in D-sharp Minor. BWV 853 between Peludes in E-flat Minor and E major? As he likewise does with the Prelude and Fugue in A-flat Major, BWV 862, inserting them between the Fugue in G Minor and the Prelude in G-sharp Minor? The reason is that D-sharp minor has historically been seldom-used by composers because of the six sharps in its key signature, and its accompanying prelude is in the enharmonic key of E-flat Minor. Presumably ,it sounds more euphonious that way. As for A-flat Major, a key first used extensively in the romantic era, I don‟t know the reason for its placement here, but present-day artists like Aaron Pilsan frequently reserve the right to move these pieces around for the sake of better expressiveness and audience communication, two factors of which Pilsan is keenly aware. Finally, what could Bach possibly have done for an encore after WTC, Book I? Just wait until Pilsan releases Book II, and you will find out!