Boston Baroque - Biber: The Mystery Sonatas - Audiophile Audition

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber today is remembered as one of the great virtuosos of the middle baroque and an important innovator in Germanic violin composition. And among his surviving works, this collection, the Sonatas of the Mystery of the Rosary, receive a lot of attention due to their baroqueness. Each of the sonatas is based, it would seem, on a prayer from the Rosary. The printing of the collection was made with scenes depicting stories from the life of Christ. Some consider the pieces as musical meditations.

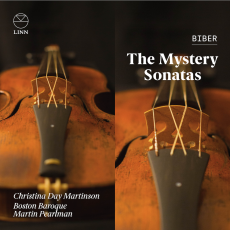

Beyond the suggestion of these sonatas as program music, these sonatas are more curious because of Biber’s use of string mistuning, often called scordatura, from the Italian. Only the first and last pieces use a normally-tuned violin; the others vary the tuning of one or more strings which promote different chordal possibilities, but moreover, change the sonic quality of the instrument. As depicted on this cover, the most interesting sonata for scordatura is the eleventh sonata, the Resurrection. The performer must cross the middle two strings, forming a “cross” between the tailpiece and bridge.

Biber’s writing is very clearly an example of the high art of the stylus phantasticus. The sections within each sonata vary in tempo and style, seemingly telling a story. But the Mystery Sonatas are far less “programmatic” than say, his Sonata representativa, where we hear various animals, including a cat.

A good number of recordings of these pieces exist in the catalog. Tempo is one variable, of course, but more often, editions differentiate themselves in the choices made for the basso continuo line. Ms. Martinson and her colleagues from Boston Baroque adopt a common practice by employing different colors for each sonata, changing up the keyboard instruments and other supporting bass instruments. Harpsichord, organ, theorbo, guitar, and cello make up this recording’s instrumentarium. Ms. Martinson also employs more than one violin, another common practice, because of the requirement of different tunings for different sonatas when played in sequence. (Violins need time to adjust to the different tensions introduced by the tunings as a prerequisite for staying in tune.)

Linn has a reputation for the quality of its recordings, and in this one they’ve opted for a solution atypical of most. Listening with headphones reveals some different miking strategies, especially so in the first sonata. The violin sound is so upfront, and seemingly positioned dead-center. At times the sound comes off like a monophonic recording. Later sonatas apparently used different positioning of players and microphones. But an extreme dryness to the sound is a trademark of both CDs. While it may reflect the solemn nature of a private playing for prayer and reflection in a small chamber, it is also not as forgiving to the performers in matters of intonation and in providing dynamic contrast.

Given more acoustical space, one of their more successful readings, the thirteenth sonata, The Descent of the Holy Ghost, would have truly shined. The gifts of Ms. Martinson are on full display. I’m inclined to believe that a live performance might have been an altogether more successful affair. Listening with loudspeakers in a larger room offers a compromise between the extreme intimacy of headphones and an imagined performance auditorium.

In order for us to appreciate the different tunings, Ms. Martinson plays the notes of the open strings ahead of each sonata. While this may be of interest to some listeners, I wished that Linn had put this onto separate tracks so they could be programmed-out. It reminded me of another recording of the sonatas by Pavlo Beznosuik, where readings of the rosary prayers were included in the recording. Thankfully, these did appear on different tracks and weren’t a requirement when listening to the music time after time.

The performances are solid, with Ms. Martinson quite adept at tackling the challenges. Comparing Boston Baroque to other recordings, the continuo team takes a conservative approach in this recording. And as a team, the ensemble plays things safe. When I re-auditioned recordings by violinist Patrick Bismuth, violinist Reinhard Goebel, or the more recent recording by violinist Hèléne Schmitt, these revealed more dialog between the entire ensembles employed. These are stylistic differences worth noting that may appeal to listeners in different ways.

Conservatism in interpretation too is present in the violin part in a some tracks. The most naked piece is the final “Guardian Angel” passacaglia, written for solo violin. For my ears, the interpretation is a bit too flat to qualify for my desert island choice. All the notes are there, but at times it feels too impersonal, too much a slave to a metronome. There’s value, though, in this difference too. That’s a symptom of a baroque text: much is left to the performing artist and differences among recordings help us, I believe, appreciate the gamut of interpretive possibilities.

The booklet, notes, and packaging are luxuriously first rate.