Duo Pleyel - Schubert: Lebensstürme; Music for piano four-hands - Early Music Review

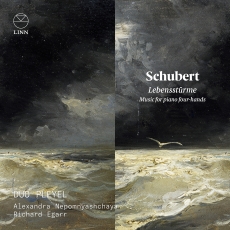

As with most other mediums in which he worked, Schubert left a large legacy of music for piano four-hands, extending as it does to some sixty works. Largely little known today, most were composed for domestic use at the ‘Schubertiads’ hosted by the composer’s Viennese friends. The present selection includes two works dating from 1818, the Rondo in D, D. 608 and the Sonata in B flat, D. 617 along with three from 1828, the year of his death: the Rondo in A, D. 951; the so-called ‘Lebensstürme’ Allegro in A minor, D. 947; and his undoubted masterpiece in the form, the Fantasie in F minor, D. 940. They are performed by the Duo Pleyel (Alexandra Nepomnyashchaya and Richard Egarr) on a beautiful Pleyel fortepiano of 1848, an instrument capable of a range extending from the massive quasi-orchestral sonorities at times asked from it in D. 947 and D. 940 to pearl-like pianissimo cascades descending from high in the treble register, D. 951, in particular, providing exquisite examples. Above all, it demonstrates across the range a variety of colour and nuance not possible to achieve on a modern piano

In the course of a brief but interesting note, Egarr quotes Schubert as claiming that there is ‘no such thing as happy music’, a highly romantic concept that the 21-year-old composer himself contradicted to a considerable extent in D. 608 and D. 617. The Rondo is founded on a perky theme with the character of a German Dance and if there are later disturbed interludes, it is the warm, poetic glow of the final episode that lingers more in the mind. Likewise, the B-flat Sonata opens with an innocuous flowing theme, played here with beguiling, unaffected charm, even if the modulations of the development do wander through unsettled, briefly stormy territory. The main theme of the central Andante con moto occupies sad, ambiguous territory temporarily assuaged by the lovely lyrical secondary idea, while the animated Allegretto offers up the opportunity for Duo Pleyel to demonstrate virtuosity with their fleet and agile fingerwork.

The main theme of the A-major Rondo, too, offers up a mood of contented innocence, perhaps redolent of one of the happier early songs in Die Schöne Müllerin, though the first episode moves to fantasia-like uncertainly. The magnificent ‘Lebensstürme’ (the storms of life) movement, cast in sonata form, displays both instrument and performers at their grandest, the big, immensely impressive sonority matched by playing of magisterial authority. The magnificent Fantasie opens with one of those heaven-sent Schubertian melodies that occupies a fragile place between nostalgic, sad reminiscence and the Elysian fields. Thereafter the work becomes an epic, twenty minutes of continuous music that veers from dance to chords as fierce and jagged as bleak mountain peaks, from playful shimmering scalic showers to a contrapuntal development of the opening theme as uncompromising as anything Bach wrote.

It should already be apparent from the above that the performances are richly rewarding. Technically near-flawless – I noticed tiny moments of blurring of texture – with a judicious choice of tempo and highly sensitive to the wide emotional range, they can be recommended without reservation. And if you don’t know the music, especially the late works, then it is high time you made its acquaintance!