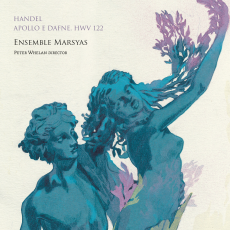

Ensemble Marsyas - Handel: Apollo e Dafne - Opera News

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL’S treatment of the Apollo and Daphne myth takes the form of a secular cantata, begun during his early-career sojourn in Venice and finished once he returned to Hanover in 1710. If it’s not one of the composer’s most exceptional pieces, Apollo e Dafne does provide pleasurable listening. (What Handel work doesn’t?!) It depicts the god first boasting that he can resist Cupid’s arrow, only to find himself relentlessly wooing the nymph Dafne. She’s transformed into a laurel tree, and the work ends with Apollo proclaiming his wish that all heroes wear a crown of laurel in his beloved’s honor.

The arias initially present Apollo’s imperturbably swaggering confidence and Dafne’s maidenly sweetness (the latter’s entrance, accompanied by an exquisite solo oboe, is one of the piece’s greatest delights). In resisting Apollo, Dafne’s second aria reveals her determined feistiness, as does her response to Apollo in their duets: he urges, “Soften that harsh severity,” while she declares, “To die is better than to lose my honor.” Apollo responds to Dafne’s transformation with a final aria exuding unexpectedly touching dignity and gentleness.

This performance’s two singers exhibit excellent stylistic instincts and an admirable musical rapport. I hope we’ll be hearing much more on CD from soprano Mhairi Lawson, for her sound is entrancing—unfailingly clear-toned, but also sufficiently colorful to hold one’s attention in every phrase. When needed she can shade her timbre to match the oboe with notable skill, she has a trill (hooray!), and she’s flexible.

Apollo is the dominant figure musically (he gets five arias to Dafne’s three), and both the seductive and aggressive elements of the role are aptly conveyed by bass Callum Thorpe. He possesses an imposing instrument, but not once does it overwhelm the music. The voice lacks consistent ease and beauty at the top of Thorpe’s considerable range (especially during the second aria, in which the leaping vocal line is especially challenging and certain passages sit uncomfortably high for most basses), but Thorpe compensates with his highly impressive command of coloratura.

Although it would have been lovely to fill out the disc with some little-known Handel arias for soprano and/or bass, Linn has opted for Handel’s most extended and elaborate overture—twenty-two minutes, six movements (with the bassoon and especially the oboe particularly highlighted). It’s from Il Pastor Fido (1712), Handel’s second stage work for London. Also included are two F-major items, identified by the composer as “arias”—charming and buoyant, showcasing double horns and double oboes, dating from the mid 1720s.

Covering itself with glory in all the music heard here is the Ensemble Marsyas, formed in Scotland as recently as 2011, and led here by its director and harpsichordist, Peter Whelan. Clearly superb technical accomplishment, mellifluous tone and stylistic authority are the hallmarks of Whelan and his players. Their precision and unforced vitality enhance their music-making. Listen, for example, to the first allegro movement of the Pastor Fido overture; it’s quite delicious.

In addition to the cantata’s text and translation, the booklet includes David Vickers’s wonderfully detailed essay, vital for the many listeners for whom this music will be unfamiliar.