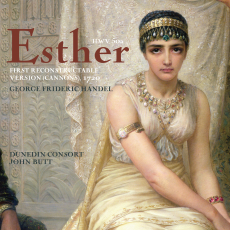

Esther - Dunedin Consort - Audiophile Audition

Esther is the first real English oratorio, not Handel's first, but his first in the language of his adopted land and his first of consequence. The libretto, most likely but not definitively by John Arbuthnot, focuses on some of the more prominent features of the story as contained in the bible, and alluded to in the Septuagint (Greek) version as well, which has some additions. Basically the story revolves around the substitution of Esther for the disobedient Queen Vashti, and the consequent saving of the Jews from massacre at the hands of Haman, chief minister of the Persian King Ahasuerus (Xerses I). Though the story is thoroughly biblical, the source material was taken from Racine's 1689 Biblical play of the same name, translated into English by Thomas Brereton.

At the time sacred oratorios were forbidden in the theater in England, which made it fortunate that Handel most likely was able to secure a private performance at Cannons, the lavish country estate of James Brydges, the Duke of Chandos. Though this is not certain, what is certain is that the original 1718 edition used almost exactly the same forces as that found in his masque of the same year, Acis and Galatea. Since a performance of Esther would not have been acceptable at this time, it makes sense that Handel's first excursion into the new world of sacred concert performance be done "under wraps" as it were.

It should be pointed out that there has been, until now, no official "1720" edition of this work. Handel revised it in 1732 because there were rumors of an unauthorized production, and copyright laws being somewhat non-existent then it was deemed expedient to revamp the piece. Of the five or so existing recordings, none uses the 1732 revision, oddly enough, while Christophers and Hogwood both use 1718. What John Butt has done here is to create a "recoverable" edition from the earliest sources possible, and from documentation that suggests a sea change had already taken place by 1720 which served as the basis for the 1732 version. The notes are thorough and interesting, while the data itself is rather hard to follow. As in so many of these types of reconstructions, many assumptions are made and educated guesses followed. No matter what one thinks of the theory behind it, the results are very nice indeed, the "masque" of the original production fully cast to the wind while the "oratorio" finally takes shape in its fullest form, especially as the work progressed towards the last bars.

All the soloists are excellent, doubling as the choir, while the orchestra follows the "expanded" forces-though not really documented, again assumed-that might have occurred as Handel's conception of the work grew into a larger stature. Surround sound is excellent, vibrant and expansive.