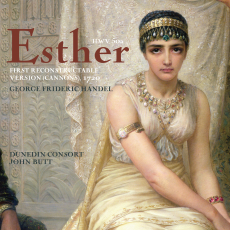

Esther - Dunedin Consort - Early Music

Most of Handel's major works were composed within a matter of months, if not weeks, but Esther, the earliest of his English oratorios, took rather longer. Its first London performance took place in 1732, but its roots go back some 14 years, to Handel's period of service at Cannons. The original score, composed in 1718 for the same forces as Acis and Galatea, is not reconstructable, for fortunately that is not the case with the larger-scale revision he make two years later - and the Dunedin Consort's George Frideric Handel: Esther HWV50a, First reconstructable version (Cannons), 1720 (Linn CKD 397, rec 2011, 100') is its premiere recording. As well as containing much splendid music, the piece throws fascinating light on the evolutionof the Handelian sacred oratorio, each act effectively documenting one of three separate influences that combined to produce the form that can be seen as the cornerstone of the English non-liturgical choral repertory. Act 1 comes over more as serenata than drama, its two tableau-like scenes presenting first the proclamation by Haman (evil aide-de-camp to Assuerus, King of Persia) of the forthcoming massacre of the country's Jews, and then the Israelies' horrified yet resigned realisation that Assuerus's marriage to Esther, their leader Mordechai's sister, has done nothing to end their persecution. Much of the music in fact derives from the 1718 version, so it is not surprising that Haman's fiercely implacable aria ‘Pluck root and branch from out the land', magnificently sung by Matthew Brook, has strong overtones of Polyphemus - though Acis offers the chorus nothing so virulent as the Persians' ‘Shall we the God of Israel fear?', which the Dunedin Consort's singers spit out with chilling malevolence. Notably clear enunciation is indeed one of the hallmarks of this recording; it also gives both Robin Blaze's singing of the Israelite priest's lament ‘O Jordan, Jordan, sacred tide', and the plangent chorus ‘Ye sons on Israel mourn', an extra sense of tragedy.

Act 2 is more dramatic, as Mordechai persuades the terrified Esther to beseech the King for mercy; when she faints in his presence, he sings of his love for her and promises to grant her every request - and on regaining consciousness she invites both him and Haman to a feast. Handel drew much of this music from his Brockes Passion, and it is indeed from that German tradition that it derives its air of intimate sensibility and human reality. This is beautifully exemplified in the intense solemnity of ‘Dread not, righteous Queen', Mordechai's last-ditch appeal to Esther, as well as in the youthful nervous naivety of her ‘Tears assist me', and the exquisitely characterized duet ‘Who calls my parting soul', in which her threadlike voice as she comes round is met by Assuerus's overflowing loving concern, all above a tremulously throbbing string accompaniment. The chorus has little to do in this act, but in Act 3 it comes into its own in a way that clearly foreshadows its key dual role in Handel's mature oratorios as commentators as well as participants - the magnificent triumphal finale even seems to look forward to the choral grandeurs of Israel in Egypt. This procession of choruses follows Esther's feast, in which she makes her appeal to the King, who, realizing that haman had issued the brutal decree entirely off his own bat, immediately sentences him to death, thus enabling Handel to show off his operatic skills. Both Haman's aria ‘How art thou fall'n', which combines nauseatingly self-pitying pleas for mercy with the fury of a wild beast in its death-throes, all over an inexorably pitiless dotted accompaniment, and her denunciatory ‘Flatt'ring tongue' , in which the unsophisticated girl audibly blossoms into a regally self-possessed young woman, are fine examples of Handel's powers of writing psychologically convincing musical characterization, Brooke's and Susan Hamilton's respective performances make abundantly clear. This early version of Esther is not just a curiosity, but a fine work in its own right; John Butt and his performers are to be congratulated on bringing it to life in a recording that no Handel connoisseur will want to be without.