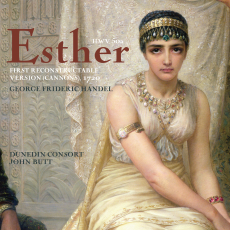

Esther - Dunedin Consort - Gramophone Session Report

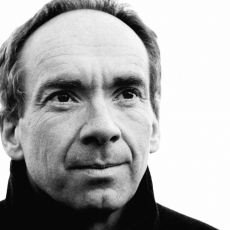

It's a tranquil pleasure to stroll the streets of Edinburgh on the way to Greyfriars Kirk during cool sunny weather. The first church in the Scottish capital city to be built after the Reformation, it attracts many tourists because of the legend of Greyfriars Bobby, the loyal Skye terrier who reputedly sat every day on the grave of his master. The broader cultural, political and religious history of Scotland is commemorated by other significant monuments in the graveyard, such as memorials to leading Scottish poets, architects and scientists. This week, though, the church has been taken over by the Dunedin Consort and Players. Director and harpsichordist John Butt hopes to construct a new kind of artistic monument inside the church: a recording of Handel's first English oratorio, Esther, which adopts significant new research into the score as well as the performing forces used for its performance at Cannons in c1720.

Christopher Hogwood and Harry Christophers both made excellent recordings of Esther before new evidence came to light about its peculiar genesis and text. A few years ago, one musician who appeared on both versions confided to me that he had never actually performed the oratorio all the way through. To avoid this pitfall, Linn's producer and engineer, Philip Hobbs, spends the first day setting 16 microphones while the performers rehearse. All participants swiftly acquire a rounded grasp of the dramatic shape and musical flow of Esther. Some musicians are only playing in a few numbers but nobody seems to gets bored. As viola player Jane Rogers excitedly remarks, ‘Wow, what a great piece! But I'm one of those strange kind of folk who actually love to listen when I'm not playing.' That evening, a private concert ‘It's fantastic fun singing in the choruses but I have to leave enough in the tank for my arias' - James Gilchrist performance is given for an audience of friends and sponsors. The uncluttered interior of Greyfriars is elegantly simple and during the concert the summer evening light continues to stream through the modest stained-glass windows. The Dunedin Consort have three artistic directors: co-founder and principal soprano Susan Hamilton (who sings Esther), Baroque music polymath and harpsichordist John Butt, and also their recording producer Hobbs. In the vestry-turned-control room after the concert, Hobbs enthuses that some of the live concert recording was good enough to use in the final edit.

Butt has prepared his own new performing edition based on a thorough investigation of all the important historical, musical and literary sources, and Hobbs has already started scribbling annotations on his copy of the score that will guide him during the editing process much later on.

The 11 singers and orchestra of 20 are delighted by their labours. Dunedin stalwarts Hamilton, Thomas Hobbs and Matthew Brook play prominent parts; Brook's performance of the villain Haman's ‘Turn not, O Queen' transfixes everyone, and Thomas Hobbs's perfectionism is evident in his self-critical responses in the control room to hearing his own singing of ‘Tune your harps'; the players responsible for the pizzicato strings and oboe accompaniment huddle behind him and whisper ‘It's gorgeous!', but during playback Butt notices that the pace slows in the da capo, so they return to the church to create ‘a more elegant sense of movement'. Harpist Frances Kelly plays nimble solos in ‘Praise the Lord with cheerful voice', sung by teenager Electra Lochhead, one of Hamilton's pupils at St Mary's Music School. In advance of Lochhead's session, Hamilton listens to the live concert playback and makes constructive preparations; she suggests that ‘More "w" in ‘choir' would be ideal', and tells me that she is impressed that ‘you only have to tell her something once and she does it - she's incredibly bright and quick'.

Robin Blaze and James Gilchrist are making their first recording with the Dunedins and are having a great time. The splendid chorus ‘Jehovah crown'd with glory bright' has an exhilarating introduction for Blaze's High Priest, with gutsy horns from Anneke Scott and Joe Walters (who tell me that Butt has simply given them a free hand to go to town on it). There's fantastic camaraderie among the ranks and plenty of irreverent laughs. As Gilchrist admits, ‘It's fantastic fun singing in the choruses but I've got to be careful not to overdo it so that there's enough left in the tank for when I record my arias.' Butt's extrovert humour causes plenty of memorable moments. During the overture, he excitedly encourages the orchestra to ‘get a bit more excited about arriving in F major!' He shrewdly reminds everyone that the chorus ‘Shall we of servitude complain' is like a minuet - the observation instantly transforms its intimacy. Butt works tirelessly to make the music conversational; he often gets the chorus to whisper the words in order to get word-stresses exactly right. The final chorus, ‘The Lord our enemy has slain', is a big Purcellian verse anthem in which trumpeter Paul Sharp makes his only appearance; he tells me he loves playing with the Dunedins and their director: ‘It's so refreshing to play for someone whose genuine scholarship gives everything we do such kudos, but who is also totally devoid of ego - that's rare and really special.'

The Dunedin Consort Work Handel's Esther (Cannons version, HWV50a) Artists Dunedin Consort and Players / John Butt (harpsichord) Venue Greyfriars Kirk, Edinburgh Producer Philip Hobbs Engineers Philip Hobbs, Calum Malcolm Dates of sessions July 9-15, 2011.