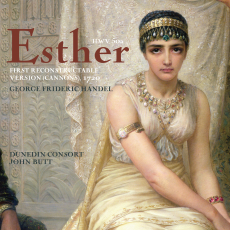

Esther - Dunedin Consort - musica Dei donum

When the interest of

English audiences in Italian opera began to wane Handel reacted by turning his

attention to English oratorio. In 1732 he performed Esther which was the start

of a long series of oratorios which he would continue to compose until the end

of his life. However, Esther was not a new work: it was the reworking of a

piece which he had composed as early as 1720 for James Brydges, Earle of

Carnarvon and later Duke of Chandos. He acted as Handel's patron and between

mid-1717 and 1718 Handel was the composer-in-residence at Cannons, the Duke's

mansion near Edgware. This resulted in various compositions, such as the

so-called Chandos Anthems, the Chandos Te Deum and the masque Acis and Galatea.

Research

has shown that even an earlier version existed which Handel started to compose

in 1718. It is impossible to say whether that was any more than a draft. In his

liner-notes John Butt remarks that much of it was "clearly discarded

during the revision". He adds that in both cases the scoring reflected the

vocal and instrumental forces which he had at his disposal at Cannons.

Esther

is available in various recordings, and that includes some attempts to perform

the version of 1720. "This recording presents the earliest recoverable

performing version of Handel's Esther,

responding to recent findings and hypotheses about the origins of the

work". Previous recordings of the first version have followed the division

into six scenes in the autograph. Handel scholar John H. Roberts, upon whose

research this version is largely based, suggests that for the performance at

Cannons this was replaced by a division into three acts. In this performance

each act comprises three scenes. A clear difference with previous recordings is

the fact that the aria 'Sing songs of praise' is omitted. It is assumed that

the recitative 'O God, who from the suckling's mouth' which is usually sung

after the aria 'Praise the Lord', was meant to introduce that aria, and replace

the aria 'Sing songs of praise'. Another notable difference is that this aria

is allocated here to the 'Israelite Boy' rather than the 'Israelite Woman'.

Esther

is different from many of Handel's oratorios in that it is not all that

dramatic. It is not a flow of events presented in a theatrical fashion, but

rather a sequence of tableaux. If you don't know the story it is hard to

understand its logic. Obviously the original audiences knew the biblical story

of Esther, Mordecai, Haman and Assuerus very well. The most dramatic part is

the second scene of the third act when Esther reveals to Assuerus Haman's plans

to kill her people. Handel's oratorios also often include a love scene. Here it

is in the second scene of the second act when Assuerus expresses his feelings

for Esther.

Acts

one and two show a kind of restraint and intimacy which could probably be

explained by the origin of a large part of the music in the second act. Here

Handel makes extensive use of music he had written only a couple of years

before in his Brockes Passion.

No less than nine numbers are based on this work. This intimacy is only

enhanced by the line-up of the ensemble: the choruses are sung with two voices

per part, the instrumental ensemble is also relatively small, with six violins,

two violas, cello and double bass, plus the usual wind instruments. It is only

in the third act that the trumpet and the horns manifest themselves.

The

Dunedin Consort delivers a performance which is outstanding throughout. The

restraint of the first two acts and the excitement of the third come off

equally well. The casting is spot-on. I have to admit that I have never really

liked James Gilchrist's singing. That is partly a matter of personal taste, but

I also regret the incessant vibrato which is rather narrow but which is

stylistically dubious. That said, he gives an admirable account of the role of

Assuerus, with a particularly impressive performance of the long aria 'O

beauteous Queen' in the second act. Susan Hamilton convincingly shows the two

sides of Esther: hesitation and fear in the second act and her anger towards

Haman in the third. Robin Blaze is probably a bit too weak in act one,

especially in the recitative 'How have our sins provok'd the Lord', which could

have been more powerful. However, there is no weakness at all in the incisive

aria 'Jehova crown'd with glory bright' which opens the last act.

Electra

Lochhead's contribution is remarkable. At the time of this recording she was

probably in her late teens as she was head chorister at St Mary's Episcopal

Cathedral in Edinburgh until September 2009. She delivers a very good

performance of the aria 'Praise the Lord with cheerful noise'. John Butt states

that this role was probably originally sung by a boy, and that is perhaps used

as an argument for this performance with a girl. However, he later writes that

it is quite possible that the whole performance in 1720 took place with trebles

and no female singers at all. From that angle there is no reason not to use an

adult soprano here. Thomas Hobbs sings the role of the First Israelite; his

aria 'Tune your harps' in the first act, with an obbligato part for oboe and

the strings playing pizzicato, is delightful. The role of Mordecai is sung by

Nicholas Mulroy; his assurance as expressed in the aria 'Dread not, righteous

Queen, the danger' in the second act comes across convincingly. Lastly, Matthew

Brook plays the villain of the piece, Haman. In the first act he perfectly

portrays his boasting: "Pluck root and branch from out the land: Shall I

the God of Israel fear?" In the third act he has to acknowledge that

indeed he should. Brook shows his softer side when he asks Esther for mercy:

"Turn not, O Queen, thy face away". Very well done.

The

choruses are impressive as far as their dramatic power is concerned. The

closing chorus which last almost twelve minutes, is quite exciting. In regard

to blending there is something to be desired, especally due to the vibrato in

some of the voices.

True

Handelians won't hesitate. They probably have already added this recording to

their collection. Others should consider it too, even if they have this

oratorio in the version of 1732. It is not only historically interesting, it is

also musically highly rewarding.