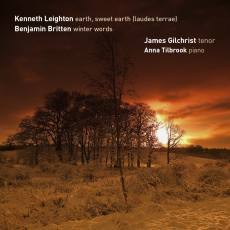

James Gilchrist - Leighton & Britten - Audio Video Club of Atlanta

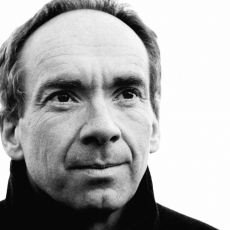

English tenor James Gilchrist started off his professional life as a doctor, and then switched to music as a full time vocation, though not without some regrets. Perhaps his training in medicine has not been at a loss, since the patient devotion, incisiveness, and respect for the well being of his patients - in this instance, composers Kenneth Leighton and Benjamin Britten - reveal character traits as important to the surgeon as the interpreter of songs. In the present recital he is joined by frequent collaborator, pianist Anna Tilbrook, in memorable accounts of Leighton's "cantata" Earth, Sweet Earth and Britten's song cycle Winter Words. Neither work is over-familiar, though both are likely to find more friends among the music loving public after the release of this recording.

Though they never actually met, there are stylistic similarities and parallels between the two composers, Leighton (1929-1988) having been influenced by Britten (1913-1976) in the development of his early vocal style. Both are concerned in the present program with the worry that, as Gilchrist expresses it, "somehow humans are losing something profoundly important, something that connects us both with the natural world and with each other, some inexpressible affinity with the very spirit of nature." That concern has become critical with the dysfunctions and conflicts of modern times. We find it in Britten's settings of eight poems by Thomas Hardy, where it reaches an early critical mass in "Midnight on the Great Northern" in the depiction of a simple rural boy bound for London traveling alone without any premonition of what may happen to him in that great city. The sense of uneasiness in the poem is echoed in the chugging movement of the piano accompaniment. "Knows your soul a sphere, O journeying boy, / Our rude realms far above," wonders the observer, "Whence with spacious vision / you mark and mete / This region of sin that you find you in, / But are not of?" In a lighter vein, "The Choirmaster's Burial" contrasts the narrow vision of the vicar, blind to the vital necessity of music in his denial of the choirmaster's last request for his favorite hymn to be sung at his graveside, and the ghostly chorus dressed in white, "like the saints in church glass," who carry out this final measure of devotion in the dead of night. - much to the vicar's amazement.

Leighton's Earth, Sweet Earth consists of a prelude from the luminous prose of John Ruskin and five settings of the incredibly rich (and incredibly challenging) poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Though the final two settings, "Hurrahing in Harvest" and "Ribblesdale," are more optimistic, the prevailing mood of the work is dark, in keeping with Hopkins' vision. "Binsey Poplars," the poet's reaction to the cutting down of majestic, ancient trees, may serve to exemplify this: "I wished to die and not to see the inscapes of the world destroyed any more." (I myself have often experienced that feeling, but never had the words to go with it, upon witnessing the lopping-off and felling of centuries-old live oaks.) Though we might console ourselves with the thought that the natural world will persist long after we humans have done ourselves in, there is another final irony, that the spoiler of the planet is also its chronicler: "And what is Earth's eye, tongue or heart else, where / Else, but in dear and dogged man?"