Jonathan Freeman-Attwood - Faure - International Record Review

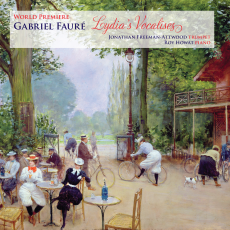

Usually when music by one of the major-league composers lies in obscurity for decades, it's because the score managed to get lost or destroyed or was concealed by some crazed relative. Music isn't usually hidden from view as a matter of deliberate policy, unless you go back to Allegri's Miserere. But there was a reason behind the sequestration of Fauré's series of Vocalises: they were used to test sight-singing at the Paris Conservatoire and so, of necessity, were kept from, well, sight. Fauré was parachuted into the directorship of the Paris Conservatoire in 1905, after heads rolled in the wake of l'affaire Ravel, when Ravel's submission was barred from the finals of the Prix de Rome competition. Roy Howat's fascinating booklet essay recounts how Fauré arrived as the new broom, sweeping clean, his zealous reforms earning him the nickname ‘Robespierre'. One of the innovations with which he sought to improve standards was this series of Vocalises, composed between 1906 and 1916 - with no thought for public performance or of publication (which, of course, would have defeated their purpose), and so they were locked away when not in use, and then fell out of use. They made their first foray into print in 2013, in a volume in the Peters Critical Edition of Fauré's complete songs, which Howat is editing, with Emily Kilpatrick.

So what are these Vocalises, and why are they performed here on a trumpet? There are 37 tracks in the relevant part of this recording: 35 vocalises book-ended by two different versions of Fauré's song ‘Lydia', Op. 4 No. 2, illustrating the proximity of these vignettes to the style of his songs. Most of them hover around the 30-second mark; only six break the minute barrier. Most of them are concerned with holding melodic shape, but Howat points to some of the traps Fauré set his students: emerging from a thicket of flats only to run into a thornbush of sharps; a sudden change of accompaniment key under a held note; enharmonic false friends, such as an A sharp tied to a B flat. You wouldn't really know when these points occur from the generally stately, dignified music itself, except when it suddenly changes direction like a Jack Russell reacting to the postman's ring.

Howat points to fanfare-link qualities in Fauré's melodic writing, and that is where the trumpet comes in. These pieces were never intended for integral performance, of course, and it's difficult to imagine them sung end to end and retaining the listener's interest. The trumpet, by contrast, can move effortlessly from one vocalise to the next, and so Jonathan Freeman-Attwood has arranged them into six short suites, to give some shape to the 40 or so minutes they take to perform. Howat further points out that you can hear in the Vocalises something of Pénélope, the opera that occupied him most during the time of their composition - but there are also tiny little flashes that remind you of other Fauré works, usually too briefly for you to put a finger on them.

Not all of the Vocalises presented here have autograph manuscripts to back up their authenticity, and indeed Fauré was not the only person on the Conservatoire staff to write them - but Howat can explain the presence of those of doubtful provenance on this CD (only four of the total): the unsigned works all bear the hallmarks of Fauré's style; and all the other composers signed their contributions (Fauré being the only member of staff who didn't have to).

Although the melody lines allow Freeman-Attwood space to soar and sweep, Howat gets less room to demonstrate his musicianship: the accompaniment is purely chordal, with no other purpose than to support the tune. Howat tackles that issue, too, pointing out that arpeggiation of the chordal support turns it quasi-instantly into the ‘rolling figurations' often found in the piano textures of Fauré's songs.

The balance of the CD is taken up with rereleases of seventeenth- and nineteenth-century French music from two earlier Linn releases, where Freeman-Attwood was accompanied by Daniel-Ben Pienaar (they were reviewed in July 2006 and July 2007). It's a pity Linn didn't keep Freeman-Attwood and Howat a little longer in the studio to add some more Fauré - for example, transcriptions of both cello sonatas for trumpet and piano might just have fitted on this disc. Even so, it's a fascinating insight into an important educational workshop, and assured performances from Freeman-Attwood and Howat also make it a musical experience in its own right. The recorded sound is in the usual Linn top-drawer league.