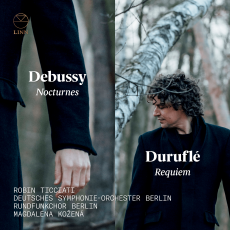

Robin Ticciati & DSO Berlin - Debussy: Nocturnes – Duruflé: Requiem - Fanfare

Robin Ticciati’s French music series continues. This is the third such disc with his Deutsche Symphony Orchestra of Berlin (previously the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and originally the RIAS Orchestra, standing for Radio In the American Sector, when Berlin was divided among the allies after the Second World War). The high profile mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená has featured in both previous issues, singing songs with orchestra by Duparc and Debussy. This program, like the previous ones, is imaginative: If you’re going to play Debussy’s Nocturnes you will need a choir of women’s voices for “Sirènes,” (unless you just leave out the third Nocturne), so why not go one further and program Maurice Duruflé’s Requiem Mass of 1947? Clearly modeled on Fauré’s gentle Requiem, the Duruflé also reveals the influence of Debussy and Ravel in its harmonies, and Debussy in its Impressionistic orchestration. This music is not far removed from the sound world of the Nocturnes, in spite of the 50-year gap between the two compositions. Duruflé (who was best known as an organist) drops the Dies irae but, like Fauré, sets the two final lines, “Pie Jesu Domine, Dona dis requiem sempiternam” as a separate movement for a vocal soloist, in this case a mezzo-soprano.

Ticciati’s performances are relaxed and lyrical, and recorded in splendid sound. Taking the Duruflé first, the sound opens up impressively in the big moments, with exhilarating climaxes in the Domine Jesu Christe and Sanctus. The radio choir blend well and are placed perfectly in the sound picture: not too close (as in Richard Hickox’s Decca recording), or too far back in a reverberant space (as in Michel Plasson’s EMI recording). Kožená sings the Pie Jesu expressively. It is as touching as the matching movement in the Fauré Requiem, if not as melodically memorable. The orchestral woodwind solos are beautifully poised throughout, and as sound the performance cannot be faulted. I do have one caveat, and that concerns the baritone soloist: namely, there isn’t one. In the smallest font imaginable, the booklet informs us “the baritone solos are performed by unison basses.” Presumably this practice had the composer’s imprimatur, but the personal element is lost—and the Requiem Mass should be nothing if not personal. John Shirley-Quirk for Hickox and Thomas Hampson for Plasson bring the dramatic solo passages in the Domine Jesu Christe to life in a manner that anonymous unison basses simply cannot. It is hard to understand why this decision was made; the notes contain no reference to it. Kožená’s contribution underlines what is missing elsewhere. Did a big-name baritone drop out at the 11th hour?

Competition in the Debussy Nocturnes abounds, of course. Ticciati’s “Nuages” does not suggest clouds so much as a solemn procession. Maybe it’s the juxtaposition of the Requiem, but the opening woodwind themes bear a striking resemblance to Gregorian chant. (Is that the missing Dies irae theme I hear from the oboe?) Ticciati treats “Fêtes” as the festive picture Debussy intended it to be, not as an opportunity to show off the orchestra’s skill. In other words, he does not press too hard or lose the rustic dance spirit at the opening. The sound (once again) opens up gloriously for the central march episode. Finally, “Sirènes” gets an evocative performance, but here for the only time I felt those creamy woodwinds might have been set a little farther away.

I am enjoying this series greatly, and the third installment is as attractive and well presented as the earlier two.