Robin Ticciati & DSO - Ravel & Duparc: Aimer et mourir - MusicWeb International

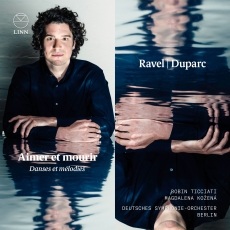

Last autumn I was delighted to review Robin Ticciati’s first release as music director with Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin consisting of works by Fauré and Debussy on Linn. Now the second release titled ‘Aimer et mourir’ - Danses et mélodies (‘Love and die’ - Dances and melodies) another attractive all-French programme of Ravel and Duparc with mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená returning to perform a selection of Duparc mélodies.

Arguably Ravel’s finest score, the one act ballet Daphnis et Chloé was written to a commission from Serge Diaghilev whose brilliant Ballets Russes were enjoying immense success during their first Paris season. The impresario was enthusiastic to secure new works for the following season from leading French composers. Ravel started work on Daphnis et Chloé in 1909, using an adaptation of the ancient Greek romance by Longus, which had been prepared by choreographer Mikhail Fokine. Progress was erratic, and the ballet didn’t reach the stage for another three years when introduced at Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris. Ravel described Daphnis as a “symphonie choréographique” though Diaghilev complained that it was more “symphonique” than “choréographique.” At a playing time of around fifty to sixty minutes it’s a lengthy work and Ravel extracted music from the ballet to make two orchestral suites. Much admired, the second of the suites from 1913, which Ticciati performs here, essentially comprises the final third scene of the ballet and concludes with the ‘Danse générale’.

Opening the suite is the rapturous and opulent evocation of daybreak (‘Lever du jour’). This enchanting depiction from Ticciati is as beautiful as it is compelling. I have to single out for special praise the delightfully extended flute solo played by Gergely Bodoky. In the voluptuous and colourful Danse Générale Ticciati creates an ecstatic atmosphere which sounds outstanding. I find Impressive the way in which Ticciati, at point 13.30, asks the players to rapidly crank up the tension and excitement, expertly underlining the wild and pagan character of the swirling bacchanalian dance. The two Daphnis et Chloé suites contain marvelous music; nonetheless it’s hard to ignore the complete ballet and for many the benchmark recording is the evergreen 1955 Symphony Hall, Boston account from Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on RCA Victor. Another ‘classic’ recording of the complete account is the lusciously dramatic 1959 Kingsway Hall, London performance from Pierre Monteux with the London Symphony Orchestra can also be positioned on the very top rank of recommended versions, fully validating Decca’s selection of it as one of its ‘Legendary Recording’ series.

Ticciati also includes on the album Ravel’s orchestral version of his Valses nobles et sentimentales. This was originally composed as a suite of eight waltzes for piano, with Louis Aubert giving its première at a Société musicale indépendante concert at Paris in 1911. The following year the composer prepared an orchestral suite for use in a ballet titled Adélaïde, ou le langage des fleurs staged in April 1912 at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris. Curiously over the years I have underestimated the score in this orchestral guise and have increasingly come to appreciate the astonishingly effective orchestration. Ticciati presides over fresh and polished playing from his Berlin players producing vivid colouration and I find especially striking the extraordinary harmonies of the third piece in the set marked Modéré.

Parisian composer Duparc is best known for his melodies, with texts from poets such as Baudelaire, Goethe and Gautier. Duparc had a mental disorder which caused him to stop composing when aged thirty-seven, although he lived until he was eighty-five. In addition, Duparc destroyed most of his music, leaving only forty pieces remaining. What Duparc did leave for posterity is greatly admired and no less a figure than Ravel viewed the mélodies as “works of genius”. Here Robin Ticciati and Magdalena Kožená have selected four mélodies in Duparc’s own orchestrations. In her career Magdalena Kožená has garnered considerable success with French repertoire and here she gets to the heart of the French text and her voice blooms beautifully. This is deliciously seductive singing from Kožená, displaying her excellent mid-range to mesmerising effect especially in the shimmering beauty of L'invitation au voyage. Tender consolation is communicated by Kožená in the nocturnal atmosphere and melancholy of Chanson triste and there’s a dusky colouration to the alluring intensity she conveys to Phidylé. Finding these Duparc mélodies of exceptional merit, to say I relish them is an understatement, not wanting the recital to end. How I wish Kožená had recorded a two or three more of the mélodies for this album. The final work on the album, Duparc’s Aux étoiles for orchestra was the surviving first movement of his Poème nocturne that the composer conducted in 1874 at a Société Nationale concert, revising it in 1910 and later destroying the other two movements. Although it is modest in length, Ticciati takes this calm and undemanding nocturne seriously, successfully evoking the atmosphere of a starry night.

Recorded in the celebrated acoustic of Jesus Christus Kirche, Dahlem there are no problems whatsoever with the recording, which is clear, relatively warm and beautifully balanced between voice and orchestra. There are helpful, easy to read notes from Roger Nichols and I’m pleased to report that sung texts with English translations are included in the booklet. There is additional room on the album to have included additional Duparc songs (as mentioned above) or maybe even his symphonic poem Lénore (1875).

Throughout this album, a masterclass in orchestral colour and atmosphere, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin under Robin Ticciati excels in this French repertoire and I look forward to more recordings in this series. Finger’s crossed that Ticciati might include some Albéric Magnard in future recordings.