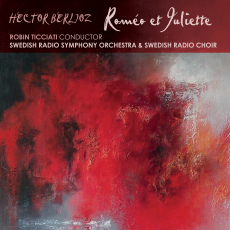

Robin Ticciati & SRSO - Berlioz: Romeo et Juliette - Audio Video Club of Atlanta

Robin Ticciati conducts the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra and Swedish Radio Choir in a performance of the complete Roméo et Juliette by Hector Berlioz that reveals both the beauties and the warts of this uneven work. First the warts, then the beauties.... Berlioz’ basic problem was that he couldn’t decide whether he was writing a symphony with voices or an opera, and his indecisiveness shows badly. His biggest difficulty, surprisingly, was in portraying Romeo and Juliet themselves. Astonishingly, he made no attempt to paraphrase the original dialogues of Shakespeare’s “star-cross’d” lovers, but instead chose to narrate the events of their meeting and the Balcony Scene, with which we’re all familiar, instead of letting R & J speak for themselves. Consequently, they are never allowed to become real, living characters. Furthermore, the libretto (presumably Belioz’ own) is filled with the sort of impossibly exalted sentiments and perfumed essences that have given French poetry a bad name. The problem with most of the world’s love poetry is that it is, ultimately, pretty banal. Love, in the last analysis, is an inarticulate feeling, rather than something that can be expressed precisely in words. In this play, Shakespeare’s love poetry proved to be the happy exception. So why did Berlioz choose to ignore it in favor of his own poetic drivel? The listener who is familiar with only the usual Four Scenes from Roméo and Juliette is completely unaware aware of these issues. In fact, you can use your home listening system’s remote to access only those tracks that make for a very satisfying purely orchestral suite: in the present instance, Romeo Alone, Feast of the Capulets, and Scène d’amour (Garden Scene), on CD1, Tr. 5-7 and the Queen Mab Scherzo, Romeo at the Vault of the Capulets, and Death of the Lovers, on CD2, Tr. 1, 3, and 4. These scenes capture the essence of the love story and its tragic ending, and are all well-rendered in the present recording. Curiously, Berlioz favored the solo male voices in this work over the female vocalist (the wonderful voice of mezzo-soprano Katija Dragojevic, as Juliette, is sadly wasted here). Tenor Andrew Staples is appropriately arch in the wickedly scathing aria taken from Mercutio’s “Queen Mab” speech, the theme of which is the illusory nature of love. And – surprise of surprises! – the best arias and the choicest dialogue are given to Friar Lawrence (bass Alistair Miles) in the Great Finale (Tr. 5-7) on CD2, where he chastises and reconciles the feuding families. This final scene, which breathes all the excitement and drama of grand opera, is a complete volte-face of the narrative-ridden earlier half of the symphony. Which again makes us wonder: just what did Hector Berlioz have in mind?