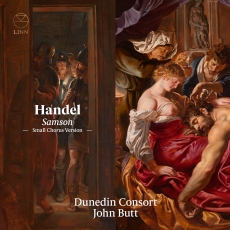

Dunedin Consort - Handel: Samson - MusicWeb International

Handel wrote Samson around the same time as Messiah, and in his day it was probably his most popular oratorio. I suspect the reason why we don’t hear it so much now is its sheer scale and length. What better method to experience it, then, than through this wonderful new Dunedin Consort recording, which brings it so life so vividly that you’ll want to return to it again and again?

In fact, a recording suits Samson for other reasons too. The text is an adaptation of Milton’s verse drama Samson Agonistes, which Milton designed for private reading, not for performance. The drama is essentially static and reflective, encouraging the reader to conceive events in his mind’s eye, so the action mostly takes place off stage and is commented on by the characters. Act 1 opens, for example, with Samson already blinded and imprisoned, and the climactic destruction of the temple takes place offstage to the accompaniment of some brilliantly busy string writing. The whole “action” consists of monologues and dialogues between characters who don’t do much more than discuss their states of mind.

Handel, therefore, creates an “opera of the mind.” An oratorio is that already, of course, but a recording even more so, and this one gives so much to not just enjoy but revel in. For one thing, the sound is top notch. Linn’s engineers have done a superb job of capturing everything with a wonderful sense of clarity and space, and their choice of venue is perfect for balancing the intimacy of the solos with the brilliance of the choruses without ever losing the colouristic detail of the orchestral playing.

Behind it all sits director John Butt, who has thought the work through from top to bottom, as he explains in a scholarly but accessible booklet note. He has given great consideration to which version to perform and how; and while I'm open to correction on this, it would seem that this version is the most encyclopaedic to have been put on disc so far. Unsurprisingly, Butt has given huge thought to the size of the forces used, and his conclusions are most interesting when it comes to the choruses. He finds evidence for two different sorts of chorus to be used: the smaller involves basically the soloists plus an extra alto, while the larger involves more forces and the addition of several boys. Typically, Butt has recorded both, and you can download both from the Linn website. The CD features only the larger chorus but, in a very generous move, if you buy the CD then you get a voucher which will allow you to download for free the version with the smaller chorus.

Whichever you choose, you’ll find a Dunedin Chorus on top form. In his most bravura style, Handel hits his audience with a Philistine chorus in praise of Dagon at the very beginning of the piece, and it sounds fantastic here, the chorus relishing every syllable and bouncing brilliantly off the trumpets and drums that blaze out of the orchestra. They are brilliantly subtle elsewhere, too, effectively bringing out the counterpoint of choruses like O first created beam or, especially, Then shall they know. The combative chorus (Israelites vs Philistines) that ends Act 2 is a thriller, and the blaze of glory that brings down the curtain after Let the Bright Seraphim is a fantastic way to end.

Having listened to both versions, I really appreciate the benefits of the smaller chorus: they sound great, and there’s something lovely about hearing these expert singers more “up close” in harmony. For sheer dramatic power, so important in this work, my own taste tended to prefer the full chorus over the smaller one, but it’s lovely that, buying the CD, you can have both, thus avoiding the agony of choice.

The orchestral picture is equally superb. Violins are light and bouncy, by turns delicate and fresh. Winds chatter convincingly and, particularly in the opening Sinfonia, horns add a welcome touch of grandeur. They aren’t used often but, when they are, the trumpets and drums make a fantastic impact, nowhere more so than in the electrically exciting final bars. Butt himself on the harpsichord underpins everything with great authority but also a twinkle in his eye, never forgetting that this is meant to be a drama, and in his hands it is never less than compelling.

It’s hard to imagine a better team of soloists, either, not least because most (if not all) of them are regular Dunedin collaborators. In the title role, Joshua Ellicott’s tenor voice is full of dramatic impulse, inhabiting the damaged hero’s character brilliantly. There is, for example, a strain of pain running through Torments, alas which works very well, and even in the recitatives you get the sense of a wounded lion looking back over his achievements from a place of agony, nowhere more so than in the interactions with Dalila. Total eclipse is deeply poignant, the high climax on “stars” sounding like a stab wound, but Why does the God of Israel sleep buzzes with a palpable uplift in energy. Just as the sun is sung with beautiful tenderness, and what a brilliantly original move of Handel's for the hero to exit on such a delicately understated aria. Hugo Hymas’ lighter tenor stands in effective contrast to Ellicott’s, and he uses the flexible agility of his tenor to magnificent effect, leaping all over the coloratura in Loud as the thunder’s awful voice and enlivening the runs of God our our fathers with great beauty. He’s equally convincing in the swagger of To song and dance we give the day, and he delivers the news of the temple’s destruction with keen dramatic sense.

Sophie Bevan brings seductive allure to the role of Dalila, with a particularly sultry colour to the middle of the voice, making her protestations of contrition sound utterly unconvincing! Her sister, Mary Bevan, uses her voice to fantastic effect, sounding alluring and sensual in Ye Men of Gaza, and using the sultry bottom of her voice every bit as effectively as the gleaming top in seductive moments like With plaintive notes or, sensationally, Let the bright seraphim. Fflur Wyn is lighter and brilliantly agile. She has a real sit-up-and-notice quality to her voice that really helps in Then free from sorrow and, particularly, the recriminations of It is not virtue. Jess Dandy’s authoritative mezzo brings great substance to the role of Micah, an Israelite woman who consoles Samson, nowhere more effectively than in her brief but fantastically long-breathed arioso Then long eternity. There is great beauty in her prayer Return, O God of Hosts! and her lament for the dead Samson is beautifully sustained.

Matthew Brook radiates authority as Manoa, Samson’s father, singing with both poignancy and great clarity in the long runs of Thy glorious deeds, and he comes into his own in the oratorio’s final section with his music of meditation as he reflects on his son’s role in bringing down the Philistines. With a completely different bass voice, I really liked the touch of try-your-chance insolence to the Harapha of Vitali Rozynko, reinforcing the drama and underlining the sense of this work as an opera of the mind that works through sound alone.

In short, this is superb, the best Handel oratorio I’ve heard in years. Its individual components are all first rate, but the cumulative whole is even more effective than the sum of its parts when you consider the packaging, the scholarship and the overall impact. The excellent historical notes from Ruth Smith only seal the deal.