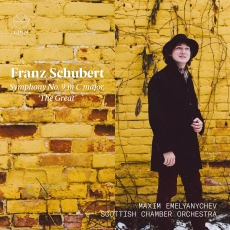

Maxim Emelyanychev & SCO - Schubert: Symphony No. 9 - Europadisc

The 31-year-old Russian conductor Maxim Emelyanychev is best known to collectors as director of the period-instrument orchestra Il Pomo d’Oro, with whom he has featured on a number of releases, mainly operatic and vocal discs from such singers as Joyce DiDonato, Franco Fagioli and Max Emanuel Cenčić. His profile is sure to become more prominent, however, following his appointment as Robin Ticciati’s successor as principal conductor of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra. This is an ensemble well-versed in period style ever since its work with its late conductor emeritus, Sir Charles Mackerras. And, as luck would have it, Emelyanychev’s first disc with his new orchestra is very much in the same territory: Schubert’s ‘Great’ C major. Mackerras memorably conducted the orchestra in this symphony (coupled with the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony) on a Telarc disc over two decades ago, and it was with this work that Emelyanychev also made his SCO debut in 2018. As it turns out, the results could hardly be more auspicious.

For many years, it was thought that the ‘Great’ C major Symphony dated from 1828 and the last months of Schubert’s life. More recent research, however, has assigned it firmly to 1825-26, and in particular to the holiday that Schubert in the summer of 1825 in Upper Austria. Here he found the happiness and health to carry him through the composition of the grand ‘public’ symphony he had longed for years to write. Most of the work on the first three movements, at least in outline, was undertaken during this pleasant and convivial time, inspired by the scenery of Upper Austria and the Salzkammergut. The result was a symphony that, in retrospect, perfectly embodies Schubert’s enthusiasm for the Naturphilosophie of Schelling and his followers, the poet brothers August and Friedrich Schlegel. (Similarly, Beethoven’s Ninth was the ultimate expression of his Enlightenment humanism, as transmitted by Schiller’s famous text on universal brotherhood.) The ‘Great’ C major is, above all, an expression of delight and awe in the natural world, most obviously in its sheer scale (the ‘heavenly lengths’ famously admired by Schumann), but also in its scoring, with woodwind, horns and trombones – all ‘outdoor’ instruments – memorably prominent.

And it is this sense of joy and contentedness that positively bubbles over into Emelyanychev’s reading. With every repeat observed (still a relative rarity, even on disc), the symphony’s proportions are respected and fully justified, while the brisk, vigorous tempi leave one in no doubt that this was a work composed in perhaps the happiest period of Schubert’s life. From the famous opening horn motif onwards, the speeds seem totally natural, the excitement palpable and infectious at the transition from Andante to Allegro ma non troppo, where Emelyanychev steps up the pulse a couple of notches to great effect. The SCO horns and Robin Williams’s excellent first oboe make their mark from the outset, but another wonder here is the fantastic nimbleness of the strings, the rhythmic engine-room of the entire work, tossing off Schubert’s unforgiving figuration as if it were the most natural thing in the world.

The second movement is taken at a proper Andante con moto (so many conductors seem to overlook the last two words), and if one perhaps longs for a little more drive towards the central climax, Emelyanychev really comes into his own in the following A major episode, the offbeat violin chords gently caressed to match the sweetness of the woodwind. Nothing quite captures the quintessentially Schubertian cheerfulness of the symphony like the earthy Scherzo and its bucolic Trio: with every repeat in place, the players clearly relish the dual challenge of Schubert’s quicksilver passagework and Emelyanychev’s bracing tempi. The reprise of the Trio’s second section especially is a moment of pure joy.

As for the Finale: however do they do it? Shaving a good 30 seconds off Mackerras’s already thrilling speed in this movement, Emelyanychev and his players impart an uncommon level of vivacity and exultation while never for a moment sounding hectic or rushed. The music builds through a carefully paced and balanced development to an unforgettable, toe-tapping, heaven-storming climax that leaves the listener beaming long after the music has stopped. It's easy to forget, too, that this isn’t a period instrument orchestra per se, but a modern one with period brass and timpani. So steeped in historically-informed practice are these musicians that every nuance of phrasing, every bow-stroke, seems infused with the classical spirit, even as Schubert looks forward to the heady late romanticism of Bruckner and Mahler. It was Mahler who wrote that ‘a symphony must be like the world’; listening to this performance, one fancies he could have been thinking of Schubert.