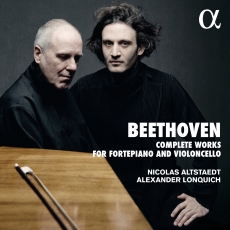

Nicolas Altstaedt & Alexander Lonquich - Beethoven: Complete Works for Fortepiano and Violoncello - US Strings

Nicolas Altstaedt’s take on Beethoven’s music for cello and piano is magical, proud, and glorious. Both he, on his 1749 gut-strung Guadagnini, and Alexander Lonquich, at an intoxicatingly bright-sounding fortepiano built by Conrad Graf in Vienna the year Beethoven died, know historical performance practice inside out. Their focus, however, lies not in style but on the extraordinary places the sounds of their instruments take them and the insights those sounds provide into the composer’s highly subjective, some- times moody, always genius romantic persona. The results engrave themselves into the listening experience as if they were inseparable from the notes on the page.

Working with a modern Luis Emilio Rodriguez Carrington bow modeled after turn-of- the-19th-century classical models, Altstaedt infuses exhilarating energy and vivid imagination into music spanning Beethoven’s three compositional periods. In order to highlight the composer’s sweeping dramatic narratives, Altstaedt crushes chords, seizes ferociously on ending flourishes, and lengthens out lines by holding music suspended in air. Altstaedt resorts to a nearly vibrato-less tone in the relatively few slow movements that leads to haunted moaning and eerie sotto voces. The double-stops he draws forth at key moments on his gut strings are sublime. He and Lonquich work together so closely that on forte unison chords Altstaedt even seems to be delaying and softening the attack, which has the effect of extending the resonance of the quickly decaying fortepiano.

Particularly notable is the Guadagnini’s low end, which is prominent both in tone and texture; in the key upward run toward the end of the first movement of Op. 69, the result is an “Emperor” Concerto–like sweep. Both Altstaedt and Lonquich treat the famous slurred repeated notes in the Scherzo as separate upbeats and beats, sometimes implied and sometimes articulated. It is a stunning effect that requires spontaneity. Their Trio is enchanting, with Altstaedt imparting a wonderful lilt to the big tune.

As the music moves to the remote landscapes of Op. 102, Altstaedt begins to use portamento more often, subtly and beautifully. The C major, with Lonquich navigating the lyrical outbursts amid the abrupt changes of angle and pace like a wizard, emerges as sheer fantasy. Their slow movement in the D major is a universe.

Their early Opus 5 sonatas and the three Variation sets are alive and charming, with Lonquich bringing out every bit of Beethoven the galant piano virtuoso and Altstaedt conveying a sense of joy that Beethoven must have felt in liberating the cello (and essentially creating the modern cello sonata); even in this nominally lighter music, the way Altstaedt and Lonquich use phrasing and rhythm to move the music forward independent of speed reveals the solidity of Beethoven’s construction.

The CDs are accompanied by an analytical/ philosophical essay, Maturity Is a Profound State of Ecstasy, by Eberhard Feltz, chamber- music professor at the Hanns Eisler School of Music in Berlin, about whom Altstaedt said, “There is no musician I have met in my life who has such clarity, insight, and depth into scores.” About Beethoven Feltz writes, “There is nothing lonely or isolated about music of genius that excludes normal human beings. No listener to these recordings should think music is only for the favored few.” On their own, these are large, important performances. Listened to while reading Feltz they are cosmic—and very human.