Handel's Acis & Galatea - Dunedin Consort - Choral Journal

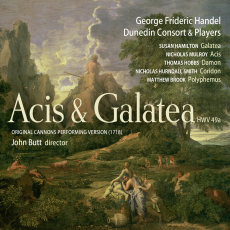

Here are two new recordings of a perennial favorite, each of which can be strongly recommended to choral directors looking for fresh ways to program Handel this year. John Butt and his Dunedin Consort have followed up on their well-received CDs of Messiah and the Bach Matthew Passion with a recreation of Acis and Galatea in the version heard at its first performance. Nicholas McGegan, also no stranger to acclaim for historically informed performances, now brings us Mendelssohn's arrangement of this same work, done around the time he was preparing the Matthew Passion for its groundbreaking 1829 revival.

Acis and Galatea itself needs little introduction. By 1718, Handel had been in England for some time but had occupied himself mainly with instrumental music and Italian opera. Aside from ceremonial works written for Queen Anne in 1713, Handel composed almost nothing in English until he took up residence at the palatial country seat of James Brydges, Earl of Carnarvon (later Duke of Chandos). For Brydges' little group of singers and players he composed the eleven so-called Chandos Anthems, the first version of Esther, and the masque Acis and Galatea. In fact, Acis apparently preceded Esther and thus ranks as Handel's first substantial dramatic work in English. It was enormously popular during the composer's lifetime, the only one of Handel's dramatic works to be published complete before his death (by John Walsh, 1743).

The story is simple: Galatea, a nymph, loves Acis, a shepherd, and he loves her. After a lengthy separation, they are united and bliss ensues. But the monstrous giant Polyphemus has also conceived an affection for Galatea, and he kills Acis. Following a series of laments, Galatea decides to use her divine powers to turn Acis into an everlasting fountain; this restores balance to the Arcadian paradise in which these events are set, and its inhabitants rejoice in Acis' transformation: "Hail! thou gentle murm'ring stream, Shepherds' pleasure, muses' theme! Through the plains still joy to rove, Murm'ring still thy gentle love."

Handel's talent for musical drama unpacked the psychology of these stock pastoral characters, suggesting that fundamental social and philosophical issues lay behind this little story. (Indeed, if we think of Polyphemus as representative of "the forces of nature," there's even an ecology lesson lurking somewhere in it.) Small wonder that the twenty-year-old Felix Mendelssohn found himself strongly drawn to the work. As a chorister in Carl Friedrich Zelter's Berlin Sing-Akademie, Mendelssohn had become acquainted with a number of Handel oratorios in the Mozart arrangements commissioned by Baron van Swieten. Along with the Dettingen Te Deum, Mendelssohn's version of Acis became his first creative treatment of a Handel work; it helped spark the nineteenth-century "Handel Renaissance" in Germany.

Handel himself had an expert but tiny ensemble at Cannons. There were no altos and no violas available, although one of Brydges' three tenors may have been a falsettist. Besides strings, the orchestra consisted of two oboes (doubling recorder) and a harpsichord. Acis can be performed, in a pinch, with just five singers and seven instrumentalists-hence its continuing popularity with graduate students in search of a "major work" for minor forces. In 1788 Mozart added clarinets, bassoons, horns, and violas. Presumably he shortened several da capo arias by omitting their repeats, a practice he had followed in his other Handel arrangements.

To Mozart's instrumentation Mendelssohn added flutes, trumpets, and timpani, and apparently revised some of the viola parts (see Wolfgang Sandberger's notes to the McGegan recording). In addition to retaining Mozart's cuts, he also cut Galatea's "As when the dove" and made other emendations and additions. (Oh, and sister Fanny devised a German text!) The result is an overall reduction of the work's running time-McGegan needs just one CD, whereas Butt needs two-but with a more colorful orchestral palette.

It seems pointless to offer a track-by-track comparison. These recordings represent two essentially different works. Suffice to say that both have their strengths. Butt uses his five soloists to form the "chorus," much as Handel did at Cannons in 1718. McGegan has nearly fifty members of the North German Radio Choir at his disposal, approximating the choral sound that Mendelssohn had in mind. Both conductors employ early-instrument specialists in their orchestras, which are of correspondingly different-and equally authentic-size and makeup (I loved the contrabassoon in McGegan's band). Both sets include high-resolution multichannel "surround" tracks as an option; the Greyfriars Kirk of Edinburgh offers a more resonant, vivid acoustic for Butt, the Stadthalle Göttingen a warmer, more enveloping sound for McGegan.

For Butt, bass Matthew Brook gives a deliciously comic reading of Polyphemus, oafish and blustering, more naïve than hateful. Yet Wolf Matthias Friedrich's more earnest portrayal, for McGegan, will seem equally valid to many, especially in the early-Romantic context of the Mendelssohn arrangement. Christoph Prégardien (McGegan) bears away the tenor honors-no surprise there-and I liked soprano Julia Kleiter (McGegan) slightly more than her counterpart Susan Hamilton, although Hamilton reveals a nascent flair for comedy in her exchanges with Brook. Given their numbers, the NDR Choir sings with more delicacy than one might anticipate. Yet Butt's five soloists create a convincing ensemble for the choruses, and they offer a dramatic immediacy of expression that scarcely any choir can match.