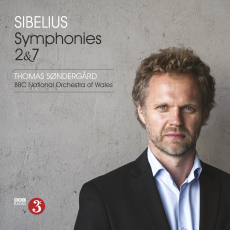

Thomas Sondergard - Sibelius: Symphonies 2 & 7 - Classical Candor

If the number of releases

in the CD catalogue is any indication, Sibelius's first two symphonies remain

his most popular, with No. 2 taking

a slight edge. This is no doubt why most conductors begin their Sibelius

symphony recording cycles with one of the first two works, which is what

Maestro Thomas Sondergard and his BBC National Orchestra of Wales do here,

giving the Second a

fairly lively, and welcome, reading. With room left over, the little Seventh Symphony is

also a welcome delight.

Finnish

composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) wrote his Symphony No. 2

in D, Op. 43 in 1902,

and the listening public quickly dubbed it his "Symphony of

Independence," although no one is sure whether Sibelius really intended

any symbolic significance in the piece. Even so, it ends in a gloriously

victorious finale that surely draws out a feeling of freedom and self-reliance

from the music. The piece begins in a generally sunny style, though, then

builds to a powerful a climax, with a flock of heroic fanfares thrown in for good

measure.

Sondergard

takes all four movements more quickly than do the conductors on any of the half

dozen recordings I had on hand for comparison, yet his tempi are not at all

breathless. Indeed, his handling of the faster sections of the first movement is

fleet and agile, the change-ups smooth and entirely natural. When he pauses

momentarily, when he increases the volume, when he goes into a hushed whisper,

or whatever, it is with purpose; and that purpose always seems to be in the

service of the music. With evenly tuned transitions from warm to cool and back,

Sondergard's interpretation places the first movement among the best you will

find.

The

second movement Sibelius marked as an Andante (moderately

slow) and ma rubato (with a flexible tempo) to allow conductors more personal

expression. The movement begins with a distant drumroll, followed by a

pizzicato section for cellos and basses. Under Sondergard this slow movement is

appropriately somber, yet he imbues the music with a degree of comfortable affection,

too, so it's not entirely melancholy. And again, Sondergard ensures that when

he reaches the intense middle section, it doesn't appear to be coming out of

nowhere but is intrinsic to the rest of the music.

Sibelius

makes the third movement a scherzo, one that provides a dazzling display of

orchestral pyrotechnics, interrupted from time to time by a slower, more

melancholy theme. The whole thing should bounce around from an admirable

liveliness to a more pastoral theme, then a stormy midsection, and a tranquil

conclusion. This fast movement is sort of the opposite in structure of the

preceding movement: instead of two slow sections enclosing a fast one, we get

two fast sections surrounding a slow one. Sondergard generates a good deal of

enthusiasm throughout this segment, keeping both the orchestra and the audience

on their toes.

In

closing, the final movement bursts forth in explosive radiance--both thrilling

and patriotic. When the third movement glides directly into the fourth,

Sondergard might have increased the horsepower just a bit more, highlighting

the heroics. Instead, he is content to let the music speak effortlessly for

itself, and perhaps he was right in doing so. He makes a rather eloquent

statement by eschewing a certain degree of exaggeration. In the final analysis,

Sondergard's treatment of Sibelius's Second Symphony is

one of the best (and best sounding) you'll find.

Completed

in 1924 the Symphony No. 7

in C major, Op. 105, was

Sibelius's final published symphony. It is notable for being in a single,

relatively brief movement. For its first performance, he called it Fantasia sinfonica No. 1, a "symphonic fantasy." It was only a

year later, when he actually published it, that he decided he would simply call

it his Symphony No. 7. Whatever, the composer said he wanted to express

in it a "joy of life and vitality with appassionato sections." To

that extent, Sondergard takes him at his word.

One

movement or not, the music flows structurally as a symphony might, just with

more seamless continuity and cogency. Sondergard's rendering of it is, frankly,

gorgeous, one of the most brilliant, moving performances I've heard. As with

the previous work, the conductor fashions it all of a piece, with nothing that

doesn't perfectly belong. And throughout all of this music, the orchestra adds

a rich, polished luster to the proceedings. It's quite becoming.

Producer

and engineer Philip Hobbs recorded the symphonies in stereo and multichannel at

BBC Hoddinot Hall, Ckardiff, UK in March 2014. Linn Records released the hybrid

SACD for both SACD stereo and multichannel and regular CD stereo playback. I

listened to the SACD two-channel stereo layer.

The sound

has a nice airy quality, with a lifelike dimensionality about it. You can hear

the orchestra not only from side to side in a realistic spread but front to

back as though actually sitting in the audience in a concert hall. This is

typical, though, of Linn Records, who usually do their utmost to make listeners

feel as though the event were live and the ensemble were actually there in

front of you. Dynamics, frequency response, impact, and overall clarity are

also quite good, with the hall itself lending a modest resonance to the

occasion.