Phantasm - Lawes: The Royal Consort - Limelight Magazine

I can, it's true, find a jazz analogy in most things, and this two-CD set of dance music from the 1630s proves to be no exception. Listening to William Lawes' The Royal Consort, I'm reminded of why hipsters digging Miles Davis and John Coltrane too often find the early 1920s recordings of King Oliver and Louis Armstrong a problem. The sheer ancientism of the music apparently operates under completely different rules and feels so utterly alien to the modern world that its archaism flips over into something entirely new: an avant-garde relic that has to be grappled with.

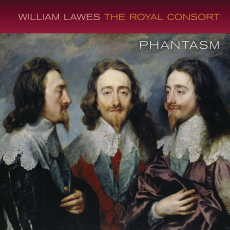

William Lawes inhabited a medieval London that was about to be irreplaceably altered by the Great Pire of 1666. He found gainful employment as a composer at the court of King Charles I and as Parliament flexed its republican instincts, he felt moved to add the prefix 'Royal' to his Consort pieces. The much good it did him though: Lawes was killed fighting for the Royalists during the Siege of Chester in 1645.

As with all genuinely great dance music - from Rameau right up to Cage - Lawes' pieces are as much about the idea of movement as they are specific invitations to the dance floor. This is a composer who revels in lopsided groupings of bars, allowing his melodic phrasings to follow their natural incline rather than being shepherded behind bar lines like sheep – a lesson in how symmetry can be overrated.

More usually recorded in the composer's own revised remake version for a larger ensemble, Oxford-based Phantasm opt to perform Lawes' original version for four viols and the lower pitched lute-like theorbo (and Organist Daniel Hyde makes a cameo appearance with some Lawes sets to the organ which, for reasons of space, could not be included on Linn's dedicated disc). The rhythmic vivacity and pungent push-pull swing of their playing rocks, while their ear for authentic period non-tempered tunings is exquisite.

This music could easily be misrepresented by an overly stolid touch or academic approach, but Lawes' contrapuntal layers become more than fluctuating details of texture: each part proudly shouts its independence while knitting into the whole.

Elizabeth Kenny's harmonically alive theorbo continue glues these rhythmic strata together, the upper parts chattering relentlessly. The emotional reach of the music - the ebullient splash of Sarabands counterpointing against moments of Dowland-like melancholia – is rich and constantly surprising, and Lawes' rhythmic and metric sleights-of-hand will indeed appeal to those who admire similar qualities in early Satchmo. Phantasm – another Hot Five.