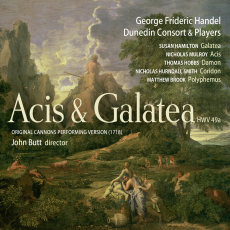

Handel's Acis & Galatea - Dunedin Consort - Fanfare

Handel composed Acis and Galatea in 1718, while house composer for James Brydges, the Earl of Carnarvon. It was not intended for the London stage, but for Cannons, the extravagant estate that Brydges was having built near Edgware, Middlesex. (It took 11 years and five architects to finish, and cost the equivalent of roughly $40 million, today.) The opera was a chamber pastorale on an English text, mainly written by John Gay and Alexander Pope, in turn derived from a tale in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The forces it used were slim, and necessarily idiosyncratic, given what Pepusch, master of musick for Brydges, could furnish at the time: one soprano and bass, three tenors, and an orchestra made up of three violinists, two oboists (who could also switch to recorders), two cellists, a bassoonist, a double bassist, and a harpsichordist.

With the exception of an inflated English-Italian pastiche of the piece given briefly in 1732, to challenge an unauthorized version of Acis mounted directly opposite Handel’s own theater, this is where matters stood until 1739. At that point Handel took his 1718 piece, divided it into two acts, expanded and altered its scoring, and made several small cuts. A few more changes were later instituted, resulting in the version that was published with the composer’s support in 1743, becoming the standard for the work.

Is there a need to hear the opera as it was presumably performed at Cannons? Not for authenticity’s sake. Handel himself had no interest in that curious 20th-century musical virtue, and like most of his contemporaries repeatedly arranged and republished works to suit the needs of the moment. But there remains a problem of scale. Acis and Galatea was initially conceived as a relatively unambitious literary and musical work, with only five solo voices that also furnished the chorus. Inflating its performing forces arguably removes some of the carefully calculated colors of the original.

John Butt, director of the proceedings under review, takes this approach. The smaller group he leads brings both vocal and instrumental soloists more to the fore. It also makes it easier on occasion to discern contrapuntal lines, as in the successive entries of “Wretched lovers!” There is less contrast, on the other hand, between soloists and chorus, and what many regard as the full splendor of the Handelian orchestra is necessarily missing.

For those who feel that the 1743 version doesn’t go far enough in increasing the orchestral forces, however, there is another new recording, featuring the 20-year-old Mendelssohn’s arrangement of Acis. (The German translation was by Felix’s sister, Fanny, a fine composer in her own right.) It was created in 1829, as the first of numerous “modern” versions of Handel that Mendelssohn was to devise in his relatively short lifespan. He enlarged the size of the orchestra by the addition of two clarinets, flutes, trumpets, bassoons, and horns each, as well as adding both timpani and violas. The strings took the part of the simple Cannons continuo, and the young composer was quite creative in reallocating parts for greater variety and his period’s own dramatic sensibilities.

“Must I my Acis still bemoan” acquires a new richness, thanks to Mendelssohn, with two lengthy concertante cello solos. “The flocks shall leave the mountains” ends with massed strings, trumpets, and flutes over furiously repetitive timpani, sounding like Beethoven, and overlaps the first chords of the plea that starts the next number, “Help, Galatea!” Trumpets and timpani add splendor, on the other hand, when applied to the duet, “Happy, happy we!” It’s not preceded by Galatea’s beautiful solo, “As when the dove laments her love,” however, because—according to Mendelssohn in a letter he wrote his former teacher, Zelter—the piece was of little dramatic appeal. He also cut occasional repeats and tried to create a better flow between the self-contained numbers.

Neither the Cannons nor Mendelssohn version of Acis is easily available from any other source at this time, so it’s a good thing both sets feature generally attractive soloists, good instrumental performances, and inspired conducting. Butt is more sensitive to details. He strikes a good balance between solo orchestral lines and vocalists, as well as taking a generally relaxed but disciplined pace to the genial score. Airs such as “Consider, fond shepherd” and “Love in her eyes sits playing” never feel pushed, while maintaining a sense of rhythmic momentum that keeps tempos from sagging. The solos of Polyphemus, one of the most delightful portrayals in Handel’s gallery of villains, gains for having all his lyrics both audible and taken slowly enough for suitable interpretation. In turn, “Wretched lovers!” leisurely unwinds its dissonances, with “Behold the monster Polypheme!” striking an admirable, dramatic counterpoint. The orchestral forces of the Dunedin Consort & Players are nimble, accurate, and highly nuanced for a small ensemble of period instruments.

McGegan plays more to the drama of Mendelssohn’s revision. He punches out the brass and percussion with rare power, but elsewhere finds a subtle elasticity in the phrasing and dynamics (“Sieh, törichter Schäfer,” the equivalent of “Consider, fond shepherd”) that strikes me as perfectly in keeping with a Romantic revisionist approach to the Baroque. The disparate forces under his command are perfectly blended rather than encouraged to stand out, with both his orchestra and chorus. The work as a whole has a darker, richer sound under McGegan’s direction, that isn’t only due to a lower pitch. Praise, too, to the Göttingen Festival Orchestra for its outstanding soloists, and the cohesion it achieves in this recently resurrected score.

Among Butt’s vocalists, his Polyphemus, Matthew Brook, is a standout. He is a master at using consonants, dynamics, and phrasing to put across character, without slighting vowels. His “O ruddier than the cherry/O sweeter than the berry” smacks its lascivious lips. The figures on “blithe” are deliberately heavy-footed, provoking a smile when he nimbly steps through appoggiaturas in the da capo repeat. The others in the cast are a mixed lot, though none are without merit. Susan Hamilton’s voice sounds poorly supported in her chest, with a vibrato that is a bit too wide at times for complete ease of listening. She boasts excellent enunciation and phrasing. Nicholas Mulroy’s tenor is dry, but able enough at negotiating the slight figures in his part. They both make a first-rate job of the coloratura in “Happy, happy we!” Thomas Hobbs has a brighter, more appealing voice than Mulroy has, with considerable agility. Nicholas Hurndall Smith combines a weak tone with good production.

Both McGegan’s Acis (Christoph Prégardien) and his Galatea (Julia Kleiter) possess more burnished voices than is typical of modern Baroque performance, but perfectly within calling distance of early-19th-century German opera, and that’s appropriate enough. Kleiter in particular is effective in the final, long-breathed dramatic pages of “Herz, der süssen Liebe Bild” (“Heart, the seat of soft delight”), where McGegan unbends in a way that was unthinkable in his trend-setting Baroque performances of more than 15 years ago. The looser production and sweeter tenor sound Michael Slattery brings to Damon (he also gets Coridon’s single air) forms an effective contrast with Prégardien. Wolf Matthias Friedrich is the one drawback, here. Where the others generally find more robust drama in their parts than Butt’s cast, Friedrich doesn’t come within a mile of Brook. He also slights note values in “Du röter als die Kirsche” (“O ruddier than the cherry”), though the pushed tempo is at fault, as well.

Linn’s clear, well-defined engineering gives some prominence to the vocalists, in an aural environment that is modestly reverberant. Carus prefers to recess its vocalists to equal footing with the orchestra in a hall that is more alive without swamping the intimacy of its continuo strings and piano. Both sets possess good liner notes.

There’s nothing else on the market at the moment that competes directly with either version of Acis. The Mendelssohn is even billed as a world premiere recording. Fortunately, each album is very good at what it does. You can buy them without extending the kind of allowances made for one-of-a-kind performances undermined by short budgets and little rehearsal time.