Aldeburgh Strings - Britten: Serenade - Voix des Arts

It may seem counterintuitive, daft, or even provocative to suggest that the foremost thrill of the human voice is its innate propensity for disaster, but is the mountain climber exhilarated more by how far up he manages to go or by how far down it is to the doldrums of mundane, earthbound life? A perverse component of the mystique of Maria Callas is the realization of proximity to failure: listening carefully to her ‘live' recordings reveals that the precarious, barely-sustained notes on high were often more vociferously cheered than the full, easy ones, the conqueror rewarded. It is the prospect of a performance going wrong that establishes the perspective that promotes enjoyment of all that goes right. In the haze of brilliantly-combusting imperfection, singers who quietly plot their own paths to self-sufficient artistic grace are often, exasperatingly, in peril of disappearing into the shadows. A good-humored, unpretentiously handsome gentleman who has intimated that he would just as happily be a match-saving footballer, English tenor Allan Clayton is no Ivory Tower-dwelling, platitude-spouting Artist. With a trophy-earning striker's balance of natural ability and unwavering discipline, he possesses a Champions League-worthy voice and an uncanny ability to find the goal despite every conceivable complication on the pitch-and with imperturbably certain pitch! Philosophy suggests that the profusion of ugliness in this world is necessary in order to give meaning to the recognition of beauty, and the same conceit can be extended to music. With this pair of very different but remarkably compatible discs, their content separated by two of the most decisive centuries in the history of Western music, Allan Clayton eschews the notion of pontificating on why he is among today's finest singers and simply sings in accordance with his gifts. Whether tackling the penalty kicks of Benjamin Britten's angular writing in the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings or the roll and cut reverses of arias from the great operas and oratorios of Georg Friedrich Händel's tenure in London, Clayton restores to the vocal recital disc a focus on the singer's voice rather than his ego. That a particular excitement of voices is their variability is what makes a singer like Allan Clayton so special: fantastically reliable, each successive phrase of his singing impresses anew. If full appreciation of the contrast of a singer like Clayton with the ranks of more ordinary troubadours means that profusions of mediocre discs must be endured, what a minuscule price this is to pay for these superb Linn and Signum Classics recordings.

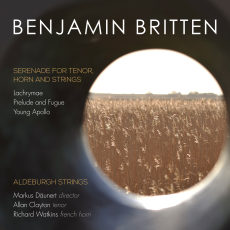

Setting the stage for Clayton's performance of the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, the Linn disc, distinguished by the sonic quality for which the label is rightly celebrated, opens with beautiful performances of Britten's Young Apollo (Opus 16), Lachrymae (Opus 48a), and Prelude and Fugue (Opus 29). Interestingly, Britten suppressed the score of Young Apollo after its 1939 première by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation forces for which it was commissioned, and the piece, inspired by John Keats's unfinished epic poem ‘Hyperion,' was not performed again until 1979, three years after the composer's death. As performed here by Aldeburgh Strings and pianist Lorenzo Soulès, whose adroit handling of the prickly writing for the keyboard is commendably unaffected, it is difficult to imagine that Britten would object to the piece's reinstatement to the repertory.

Director and concertmaster Markus Däunert leads the Aldeburgh musicians in comfortably navigating the harmonic channels of Lachrymae, a series of variations on the principal theme of John Dowland's song ‘If my complaints could passions move' in which the familiar melody of Dowland's ‘Flow my tears' is also sampled. Lachrymae was written in 1950 for viola virtuoso William Primrose and revised in 1975 for violist Cecil Aronowitz, at which time the original piano part was reimagined for string orchestra, producing the version performed on this disc. Máté Szücs, principal violist of the Berliner Philharmoniker, proves an excellent exponent of the piece in this performance, drawing from his instrument tones that recall the glowing-amber timbre of the Guarneri viola preferred by Primrose throughout much of his career. Here, too, Däunert and the Aldeburgh Strings musicians follow the composer's meanderings expertly, the sinuous textures of the music sometimes reminiscent of the ethereal writing for strings in A Midsummer Night's Dream. The melancholy that colors Dowland's songs is subtly evinced by Szücs's noble phrasing and soothed by Däunert's insightfully-gauged support.

Composed in 1943, the Opus 29 Prelude and Fugue for strings in eighteen parts is an aptly unsettled bridge between the other works on the disc and the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings, the composition of which it immediately followed. The Prelude is played with the gravitas that the music demands, each musician clearly attentive to the importance of her or his part to the Prelude's shifting tonalities and the crucial violin solo lines beautifully realized by Däunert. Performance of a fugue with an unique part for each of the eighteen instruments, a device familiar from the polyphonic masterpieces of Thomas Tallis, requires extensive resources of concentration, rhythmic precision, and uninhibited cooperation. This performance displays an abundance of these resources, the Aldeburgh Strings producing detailed, engaging vignettes that unite in a complex but marvelously coherent musical mosaic. Throughout this traversal of the Fugue, the inventiveness of Britten's contrapuntal writing is evident. Though not as widely-known as his Simple Symphony and Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge for similar forces, the Opus 29 Prelude and Fugue constitute one of Britten's most accomplished works, a distinction made audible in the performance on this disc.

It is no coincidence that horn soloist Richard Watkins occupies the Dennis Brain Chair on the faculty of the Royal Academy of Music. Continuing the legacy of Brain, at whose suggestion the Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings was composed in 1943, whilst Britten convalesced from a serious bout with measles and concurrently toiled on the libretto for his opera Peter Grimes, and Barry Tuckwell, with whom Britten recorded the Serenade two decades after its première, Watkins acquits himself impeccably in this performance of the Serenade. His easy command of the horn's infamously tricky natural harmonics, exploited to chilling effect by Britten, is nothing short of remarkable, but the technical mastery of his playing never overwhelms its innate expressivity. Especially in the Serenade's Prologue and Epilogue, entrusted solely to the horn, Watkins rises to the challenges of Britten's music spectacularly, producing a stream of even, accurately-pitched tones that fully expose the genius of the composer's writing for the instrument.

Not surprisingly, the vocal part in the Serenade was written for and first performed by Sir Peter Pears, Britten's partner in life and music and the muse for whom the composer created a succession of the finest tenor rôles in Twentieth-Century opera. With his opening phrase in ‘Pastoral,' his elocution of Charles Cotton's text shaped by an audible sensitivity to Britten's use of consonants as rhythmic markers, Clayton establishes himself as a triumphantly worthy successor to Pears. The serenity with which the younger tenor delivers the line ‘The shadows now so long do grow' ideally complements the yearning discord lurking within the music. Lord Tennyson's words in ‘Nocturne' are articulated with equal comprehension, the contrasting open and closed vowels in the lines ‘O love, they die in yon rich sky, / They faint on fill or field or river' enunciated with clarity that enhances the gnawing harmonic complexity of Britten's setting. With a haunting text by William Blake, ‘Elegy' is among its composer's most poignant inspirations, its vocal line so meticulously sculpted for Pears's sinewy voice that even speaking the words in time to the music seems to recreate the graceful whirr of his singing. Clayton's voice is both more beautiful and more secure throughout the range than Pears's, but the forthrightness with which he limns the distress of lines like ‘O rose, thou art sick' recalls Pears's interpretive perspicuity.

The anonymous text drawn from the Lyke-Wake Dirge melds with Britten's music in ‘Dirge' with a sensual desolation that gains pathos from the sincerity with which Clayton sings ‘If even thou gavest hosen and shoon.' Like all of its companion movements in the Serenade, ‘Hymn' receives from tenor and musicians a reading of unflappable musicality and intelligence, their seamless collaboration yielding extraordinary dividends. Here, too, Clayton's use of text, in this instance by Ben Jonson, heightens the impact of the composer's harmonies, so carefully crafted to complement the nuances of the words, not least in the passage beginning with ‘Earth, let not thy envious shade.' Tapping the vein of melody in John Keats's verse, ‘Sonnet' inspires singer and musicians to starkly persuasive, startlingly lucid music making, the sting of the lines ‘Turn the key deftly in the oilèd wards, / And seal the hushèd / Casket of my Soul' surging from the disc. In the Serenade and in Britten's music in general, the foremost pleasures are almost always found in the dialogues among artists instigated by the intimacy of even his most expansively-constructed scores. Forcing nothing, Clayton and his colleagues here converse with the camaraderie of beloved friends. Is this not the truest essence of what music is meant to achieve?