Dunedin Consort - Handel: Samson - Planet Hugill

Showcasing the latest research into the performing forces Handel used, this new recording is a thoughtful response to Handel's music

Despite his popularity, and the excellent survival of his manuscripts, there is much we do not know about Handel and his music. The mechanical details of exactly who performed what, and with what forces, are often rather lacking. Researches are continuing, and new discoveries being made. Recently a new scholarly edition of Handel's Brockes Passion was created and recorded by the Academy of Ancient Music with forces similar in size to those used in Hamburg for the work's premiere [see my review].

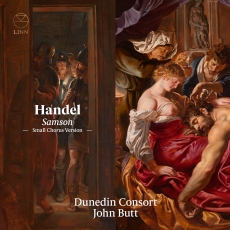

Now John Butt and the Dunedin Consort have turned their attention to Handel's Samson, his great 1743 oratorio based on Milton's Samson Agonistes. Butt has concentrated his attentions on two areas. First, they record the very full original version of oratorio, a work which Handel revived a number of times and which he routinely cut in later performances [it is a long work, Butt's recording lasts some three hours 24 minutes]. Secondly there is the issue of the forces used. Handel's choirs are badly documented, except for that used for the Foundling Hospital performances of Messiah. There is some indication that for large scale performances, Handel's soloists sang along with the choir of men and boys, to create a mixed ensemble of a type not commonly encountered in modern life. But there are also suggestions that at some later performances, perhaps for reasons of economy or logistics (the men and boys being not available), a choir of only soloists was used. And bear in mind that the premiere of Samson had eight soloists, a rather handy three sopranos, one contralto, two tenors and two basses.

John Butt and the Dunedin Consort's recording of Handel's Samson is on Linn Records, with Joshua Ellicott as Samson, Jess Dandy as Micah, Matthew Brook as Manoa, Vitali Rozynko as Harapha, Sophie Bevan as Dalila, Hugo Hymas, Mary Bevan and Fflur Wyn, with the Tiffin Boys' Choir.

Handel wrote Samson in 1743, after his return from Dublin where he premiered Messiah in 1742 (which was coolly received in London in 1743). The success of the Milton-based oratorio L'Allegro in 1740 led Newburgh Hamilton (who wrote the libretto to Alexander's Feast in 1736) to try to match Handel's music with Milton's words again, and it was Hamilton's idea to turn to Milton's Samson Agonistes. Though the story is based on the Book of Judges, Hamilton's libretto sticks closely to Milton (only taking the idea of the initial Philistine festival from the Bible), but changes Milton too, most notably in softening the role of Dalila (Winton Dean suggests that this may be at Handel's insistence). And it was Hamilton who introduced the Philistine choruses (the chorus in Milton is Israelite throughout), thus giving Handel the sort of contrast he liked, which comes out most notably in the double chorus of Philistines and Israelites. The structure of the work owes something to Saul, in that work is framed by an opening festival and a closing elegy.

It is perhaps worth noting, that Handel frames the music in a way which makes the Philistines as approachable as the Israelites, something lacking in Milton, who evidently hated the Philistines. Nor does Handel follow Milton's moral tone with his hatred of sin. So, to quote Winton Dean, Dalila 'is highly spiced, but deceitful only in the coaxing game of love'. Evidently Mendelssohn was rather shocked by her music, as detailed in a somewhat priggish letter to Sterndale Bennett in 1839!

After the first run of eight performances of Samson in 1743 (a total rarely achieved by Handel in oratorios), Handel revived the work in nine subsequent seasons, and always there were changes. Winton Dean details the complex sequence of cut and restoration in his book Handel's Dramatic Oratorios and Masques, and more recent scores of the oratorio edited by Donald Burrows for Novello (2005), and by Hans Dieter Clausen for Barenreiter (2011) have established the constituent parts of various versions. There is perhaps no ideal version of Samson; it can be argued that the first act is rather slow, and it is also significant that Handel never cut anything after the Dalila scene. But it is good to have every note of the oratorio as Handel first performed it, even though it is perhaps too long for every day performance. But that, surely, is what recording is for.

For the disc, the choruses are recorded by an ensemble of soloists, joined by eight further singers, plus eleven boys from the Tiffin Boys Choir on the top line. The results are intriguing, they give us the small scale professional choral sound which we are used to, but with a slight admixture of the ensemble of soloists which we are becoming used to in Bach (Butt and the Dunedin Consort have recorded Bach's passions using just an ensemble of soloists for the chorusese). And the boys add a brightness and a clarity to the top line, they are very definitely there. The result is a powerful set of choruses, and for these alone the disc is worth buying. Handel wrote some terrific numbers for the chorus here, and the ensemble on the disc really do them justice. And if you want a change, then you can download the choruses recorded just by nine soloists (to the eight used in the piece, Butt adds a second alto).

One of complete unknowables about Handel performance is what his soloists actually sounded like. The title role in Samson is one which has tended to be viewed at the more heroic end of the scale, yet the first Samson was John Beard, for whom Handel also wrote the title wrote in Jephtha, yet Beard routinely sang in Messiah and oratorios like L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato. The likelihood of Beard sounding like Jon Vickers, the great dramatic tenor who sang the role at Covent Garden in 1985, is very unlikely, and the fact that recordings of the work have used tenors such as Anthony Rolfe Johnson, Robert Tear, Tom Randle gives you a feel for the style of voice required.

Here we have Joshua Ellicott, a lyric tenor known for his Evangelist in Bach's passions as well as later 19th century repertoire. Here he brings a real sense of intimacy to the role. It is worth bearing in mind that Milton's Samson Agonistes was originally written to be read, not to be acted on stage, and the oratorio still follows this in that nothing really happens. The work is a series of moral dialogues, expounding Samson's state of mind by presenting him with figures from his past. When the curtain goes up he is already captured by the Philistines, and the denoument happens off stage. We are in Samson's head, as much as we are anywhere and Ellicott's reading really brings this over. His account of 'Total Eclipse' starts in the most intimate, moving manner, and then grows into something approaching operatic. Ellicott's voice is a lyric one, with the remarkable staying power to cope with the long role. It is not a luxurious voice, but expressively characterful and with an ability to bring a remarkable sense of focussed power to the vocal line when needed. His final aria in act one, 'Why does the God of Israel sleep' is strong in character, without being strictly heroic, and his contributions to Act Two, where Samson is challenged by the Philistine champion Harapha and by his former love Dalial, are finely vigorous. He raises his spirit in Act Three, but in a way which eschews any bravura heroics, so that we have a thoughtful reading.

Samson's sidekick Micah can often seem something of a moralising bore, constantly popping up and commenting. But when sung by Jess Dandy, nothing is further from the truth. Dandy, a true contralto, brings a beautifully dignified sense of phrasing to everything she sings, whatever the emotion you are always moved by the way she phrases the music. She makes Micah dignified and sober, but never boring.

Samson's father Manoah is here sung by Matthew Brook. All the soloists bring out the words in a most admirable fashion, not just with clear diction but with the necessary expressivity. The intention of this style of oratorio was a moral one, there was a story to tell, a point to make and words are essential. But Brook seems to have the gift in spades, and his way of combining text and music is masterly and makes even his recitatives powerfully expressive tools. Yet he can also bring a virile swagger to the music when needed as well!

There is even more swagger from Vitali Rozynko as Harapha, the self confident hero of the Philistines who comes to taunt Samson in Act Two in a most delightful way. Harapha's appearance, with an aria with manages to be both dignified and swaggering, provokes both a vigorous aria from Samon with angular, accented vocal line and unison violins, and then a vigorous duet for the two.

Similar things happen with Dalila's earlier appearance in the Act. Sophie Bevan makes her first aria noble, finely phrased and dignified, but Samson is not convinced. There is some powerful recitative and then an aria for one of Dalila's women (probably conceived for Dalila, but as this was the musical comedy actress Kitty Clive, the aria was transferred to someone else), Samson has an aria which is something of a grave dance, but Ellicott brings a bitter edge to it, then Dalila tries again, this time another dignifed aria which turns into a lovely echo duet with one of her women. Finally she snaps, and gives a hymn to life's pleasure, here Bevan brings a terrific rhythmic snap to the melody, in a bravura display of temperament. Samson and Dalila's final duet is a vigorous piece, with both singers spitting out the words, a far cry from Saint-Saens indeed.

The smaller roles are well taken with Hugo Hymas, lyrically and characterfully popping up as an Israelite, a Philistine and a Messenger. Mary Bevan and Fflur Wyn share female extra roles between them with Mary Bevan getting the work's hit number 'Let the Bright Seraphim', sung by An Israelite Woman at the close of the oratorio.

Throughout the orchestra accompanies and partners with great panache. The orchestra is reasonably luxurious for Handel, not only do we have two oboes and two bassoons, but there are also two trumpets, two horns and timpani. We don't get the famous Dead March, that is one of the later changes, and I admit that I rather missed it, everything else is as riveting as the rest of the disc.

I have to confess that this set gradually grew on me and drew me in. On first hearing it did not seem to be the Samson of my dreams (what ever that mythical beast may be), and instead Butt's thoughtful and intelligent response to Handel's music gradually seemed to be most natural and created a finely satisfying whole. This is not Samson as quasi-operatic drama, and there is no hint of any sort of dramatic staging, instead there is a profound response to Handel's music and Milton and Newburgh Hamilton's words.