Francesco Piemontesi, SCO & Andrew Manze - Mozart: Piano Concertos 19 & 27 - Fanfare

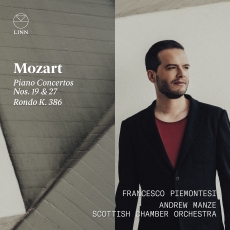

This is the second disc devoted to the last three Mozart piano concertos by the acclaimed Swiss pianist Francesco Piemontesi. Here we get the final concerto, No. 27, which was first performed in 1791, the year of Mozart’s death (it was probably the last thing he played in public). The initial album in Piemontesi’s series (if it is one) appeared in 2017 and consisted of Concertos Nos. 25 and 26. I’ve seen no reason given for why the pianist chose these three culminating works, but now we also get the ebullient Piano Concerto No. 19, K 459, which sits squarely in the miraculous run of 14 concertos that Mozart produced for himself as public virtuoso in Vienna, beginning in 1784.

Reviewing the first disc, which also involved Andrew Manze and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, I felt, like many others, that I was discovering a rising star. Now “rising” is no longer necessary. In between recording Mozart, Piemontesi experienced a rapid boost thanks to two astonishing Liszt recitals comprising the first two books of Années de pélerinage. His Mozart is quite different, naturally, showing evidence of the young pianist’s study with Alfred Brendel and, more obviously, Murray Perahia. Piemontesi’s Mozart isn’t as cool and objective as Brendel’s. What I said about the earlier disc holds true here: “Piemontesi’s style is exuberant, confident, never fussy, and buoyant enough to carry every movement on an arc of assured music-making.” (Fanfare 41:4)

For comparison, I turned to another widely praised Mozart pianist, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, whose concerto cycle on Chandos is setting the current standard. Both pianists bring the solo part alive in a winning way. But in a touchstone movement like the Allegretto middle movement of K 459, Bavouzet decidedly leans towards period style with a quicker pace, a light, dancing line, and chamber- sized accompaniment. On paper the setup for Piemonntesi looks the same, employing a chamber orchestra without vibrato in the strings, and a conductor who has a strong HIP background. But what we hear is weightier, more grounded in the bass line, and more formal.

I am not implying that this approach is less appealing, and it doesn’t feel old-fashioned. The telling advantage of Piemontesi’s recording is Linn’s wonderful sound, which makes the piano seem richer than for Bavouzet and brings the lovely woodwind scoring in Concerto No. 19 more to the fore, whereas Chandos by comparison recesses the orchestra. Another touchstone is the first-movement cadenza: Bavouzet is more restrained and Piemontesi more the extroverted virtuoso. Certainly there’s room for both stylistic approaches, and nothing undermines how beautifully the two soloists play. One influence of period style that they share, as you can hear in the finale of K 459, is vigorous, pointed accents that verge on staccato.

In advance reviews I notice an emphasis on Piemontesi’s sparkling exuberance, but this is tempered in K 595. Although in a major key (B♭), the first movement goes into the minor and wanders there, while the instrumentation lacks the trumpets and timpani that make other Mozart piano concertos feel festive. The mood of Concerto No. 27 is ambiguous, even shadowy. This gives Piemontesi scope for a nuanced touch that communicates the music’s half lights, especially in the opening movement. Bavouzet hasn’t yet reached the last concerto, so for comparison I turned to the past, Emil Gilels with Karl Böhm and the Vienna Philharmonic (DG). The mood of both performances is one of mature reflection, but Piemontesi’s touch shows considerably more finesse, and to my surprise, the Larghetto, which begins with solo piano, is fussy under Gilels, while Piemontesi is alert and forward-moving.

Filling out the new disc is the nine-minute Rondo in A, K 386, from 1782, which had a complicated history after Mozart’s death. His widow sold the manuscript to a collector, minus the final pages, which couldn’t be located. The existing pages were scattered, and the standard performing edition was Alfred Einstein’s 1936 reconstruction based on a solo piano arrangement from 1838 by the daughter of one of Mozart’s pupils. As pages of the original manuscript have turned up, the last batch being the final pages, found in the British Library in 1980, the piece has come closer to Mozart’s intentions.

These are the bare facts, which I haven’t followed up in detail as to which pianist uses which performing version—the piece remains relatively unperformed in concert as far as I know, but the discography is fairly full, with 20 pianists who have recordings in print. Piemontesi’s reading is as detailed and engaging as anyone could wish, displaying his natural feeling for making music seem spontaneous and personal.