Handel's Acis & Galatea - Dunedin Consort - International Record Review

Acis and Galatea marks a turning point in the development from a mixed-medium, largely undistinguished kind of entertainment in London's theatre life towards the later glories of Handel's dramatic oratorios and the masques. The libretto is mainly the work of John Gay and shows plentiful verbal borrowings from the then-current repertory. Distinction was in short supply in the second decade of the eighteenth century, with few composers and dramatists of talent on the scene, apart from Johann Christoph Pepusch and John Galliard in the first category, and John Hughes and Colley Cibber in the second, so the arrival of Handel, even with a masque that was privately commissioned and performed, was a major event in London's musical life. He did not come to the Ovid-based story for the first time with Acis and Galatea - he had written Acis, Galatea & Polifemo, an Italian serenata, a decade earlier, though that score left scarcely a trace on his English masque.

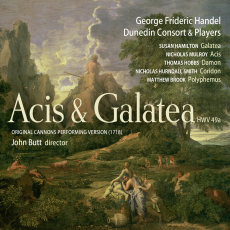

The last page of Handel's autograph of Acis and Galatea, which may have included the date of completion, is missing, and we cannot be certain when it was written and performed. The summer of 1718 is the most likely period, during Handel's appointment as resident composer to the Earl of Caernarvon (shortly to become Duke of Chandos) at Cannons in Edgeware. It was later revised and extended in the mid-1730s, but in its original modest scale (performable by five singers and a handful of string players with two oboists doubling as flautists, and continuo) it must have been well suited to a semi-staged private performance. It is in this vein that John Butt with his Dunedin Consort and Players (here 12 in number) have recorded it, following their impressive and thought-provoking set of Messiah two years earlier (it was reviewed in December 2006).

The performance is perceptive, sparkling, with crisp rhythms and neatly pointed phrasing; the tragedy comes across starkly, yet is softened by the metamorphosis of Acis into a fountain. Susan Hamilton is a charming Galatea, fresh-voiced and with pure tone. As Acis, Nicholas Mulroy is neat and accomplished, and he rises to the challenge, vocally and in terms of spirit, of standing up to the giant, then of dying with dignity. Thomas Hobbs in the role of Damon, Acis' companion, is smooth-voiced and neat, with forthright delivery. As Coridon, Polyphemus's companion, Nicholas Hurndall Smith makes the most of his one air. Charming as is the pastoral first act, it is only with the opening of the longer second act that the story takes on a serious tone, apparent right from the start with the Purcellian chorus 'Wretched lovers', which introduces stark dramatic irony following 'Happy, happy we!', the lovers' duet that ended the first act. It is from this point that musical characterization comes into play, with Handel's depiction of 'the monster Polipheme', who has also fallen for Galatea but meets with scorn from her. Polyphemus has a wide vocal (and psychological) range: 'I rage, I melt, I burn', brilliantly set by Handel, covers most of it, but there is a touch of humour too, to offset the brutishness with which he dispatched poor Acis when he hurls a mighty stone ('massy ruin') at him. Matthew Brook faces up to a real challenge, not only from the composer's demands but also from the long line of distinguished basses who have sung the role in the past. He covers the wide vocal range impressively, bringing individuality to his assumption, and has the ability so to colour his phrasing that each of those three initial verbs is appropriately shaded.

Acis has proved a popular work on the gramophone - not surprisingly, as it is a brilliant score that combines graceful melody in its best-known pastoral airs, a touching and familiar story, and rumbustious numbers for Polyphemus. Two comparatively recent versions head most people's lists: William Christie, with a small-scale but lively and affectionate reading, and Robert King, likewise full of character and spirit, and very well sung by a fine cast, with spirited orchestral playing. The team for Neville Marriner's 1977 recording is not quite as captivating, but his remains a thoroughly enjoyable, if somewhat over-decorated performance.

Linn provides an attractive booklet to accompany the outstanding new recording, with the sung texts as well as a detailed and informative introductory article by Butt, and essay on the Cannons performing version and notes on the performers. The recording (Greyfriars Kirk, Edinburgh) is spacious and well balanced. This issue is warmly recommended.