Pavlo Beznosiuk - Bach Sonatas and Partitas - Audio Video Club of Atlanta

It's a funny thing, but the Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin had never been my favorite among J. S. Bach's works for unaccompanied string instrument. My affection had always gone out, first and foremost, to the cello suites, which I've always found easy to love for their infectious themes and irrepressible rhythmic vitality. The violin works, by contrast, had always seemed cooler and more austere, more cerebral. I was all the more unprepared to embrace the new recordings by Pavlo Beznousiuk when they appeared in a handsome looking (and handsome sounding) package on the Linn label.

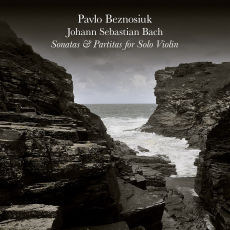

Sometimes, despite the old adage, you really can tell a book from its cover. The photos of the Cornish landscape that grace the cover art and booklet remind us, once again, that the eye can see much more from black & white photography than it can in color. The visuals may be taken as a metaphor for Beznosiuk's masterly probing of Bach's writing that gets down to the bare bones, the heart of the matter. At the same time, there is graciousness in the stylish playing on this 2-CD set that wins the listener over to the music, even when the composer is at his most relentless and uncompromising, expressing a sadness bordering on tragedy.

The six works in this set are of two types. The sonatas are in the general mold of the Italian sonata di chiesa with the structure: slow-fast-slow fast, and are therefore in the style of Corelli rather than the flashier, more animated sonata da camera style we are most accustomed to in the manner of Vivaldi. The suites are in the French style, which Bach interprets with considerable freedom. They typically begin with a stately Allemande, followed by a lively Corrente, a slow, often moody Sarabande, and then a suite of galante dances, concluding with a faster dance, usually a Gigue, first cousin to the familiar Irish jig. The types of dances and their order of occurrence were by no means set in cement, and Bach shows considerable variety here.

In Beznosiuk's hands, these six sonatas and partitas come alive as breathtaking works of the creative imagination. He generally prefers fairly brisk tempi, but can slow down to a deliberate tempo when the occasion calls for it, as it does in the deeply philosophical Grave movement at the beginning of Suite No. 2 in A Minor. He scores his points impressively and indelibly in the famous Ciaccona of Partita No. 2 in D Minor, taking us through its catalog of moods, stylistic treatments, textures and figurations as it undergoes a sea-change that makes us wonder if the music will ever end, all the while hoping against hope that it will go on forever.

While the Ciaccona is the most famous and often-performed, in all manner of arrangements and transcriptions, of the movements in this set, it is closely rivaled by the vivacious G-Minor Fugue in Suite No. 1 which is also know from its settings for organ (BWV 1039) And lute (Fugue only, BWV 1000). The Fugues in the three suites are possibly the most difficult and challenging movements in the entire set (the afore-mentioned Ciaccona notwithstanding), requiring an instrument that is normally heard playing a single musical line to create and sustain two or three parts, then bring them to the point where, as if by magic, he creates the illusion of a single melodic line. This illusion, by the way, demands the utmost of the performer's art, especially when, as in the Fugue in Suite No. 2 in a Minor, the texture becomes sufficiently dense that the performer is obliged to slow down the tempo, as Beznosiuk does here ever so slightly, in order to keep the lines clearly distinct.

I haven't mentioned the spellbinding effect of this music when it is performed as sensitively as it is here. Beznosiuk himself attests to its compelling nature when he talks of the difficulty of setting out to work on a particularly troublesome passage, in, say, the G Minor Fugue, only to find himself "playing on helplessly (but happily) to the end of the piece!"