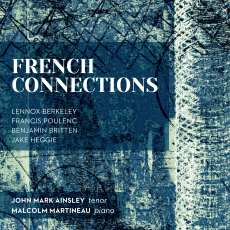

John Mark Ainsley - French Connections - Fanfare

John Mark Ainsley emerged as the first Britten tenor of the generation after Philip Langridge and Anthony Rolfe Johnson. Now 53, he is a year or two older than his compatriots Ian Bostridge and Mark Padmore. Ainsley (like the others) has sung more than just Britten. He has a considerable track record in French music, having recorded Berlioz with Charles Dutoit in the 1990s; specifically the role of Hylas in Les Troyens, the Narrator in L’enfance du Christ, and the tenor solo in the Requiem. While regarded back then as the possessor of a mellifluous light tenor voice, with a honeyed tone as its center, this new recital also reveals him (at least to this critic) as a highly intelligent, committed artist. Moreover, his vocal powers have not diminished in the least.

This cleverly conceived program contains many cross connections, as the CD’s title suggests. The English poet Wynstan Auden was an early champion of Benjamin Britten (who set Auden’s words in several compositions, notably On This Island and Paul Bunyan). Auden introduced Britten to the poetry of Donne, resulting in one of the composer’s masterpieces. The composer Lennox Berkeley was also one of Britten’s close companions in the 1930s—the two men collaborated on the orchestral suite Mont Juic—before Berkeley turned away to embrace Catholicism and marriage, about the time that Peter Pears arrived on the scene. Britten’s friend Francis Poulenc wrote most of his melodies for the baritone Pierre Bernac, who is the subject of one of Jake Heggie’s portraits in the cycle Friendly Persuasions, as are Wanda Landowska (for whom Poulenc wrote his Concert champêtre) and Paul Éluard (whose poetry Poulenc set). There are also obvious dramatic links between Heggie’s opera Dead Man Walking and Poulenc’s Dialogue des Carmélites, not to mention the purely musical influences that pass back and forth among this group of four composers.

Britten is clearly an influence on Berkeley’s writing in the Five Poems of W. H. Auden, especially in the accompaniments, so much so that the work might be construed as an homage to the younger composer. Berkeley’s spare textures, such as accompanying the vocal line with plain octaves, and the use of isolated decorative textures in the piano’s high register, recall Britten’s Winter Words composed five years earlier in 1953. Ainsley brings a strong profile and straightforward, clear tone to the Berkeley cycle, hinting at concealed depths beneath Auden’s surface detachment. For Poulenc’s Éluard settings, Tel jour telle nuit, Ainsley’s sound becomes more intimate, catching the melancholy strain in both words and music. Britten and Poulenc each contribute a setting of Shakespeare’s “Tell me, where is fancy bred....” (The Merchant of Venice, act III, scene 2). Poulenc’s setting is contemplative, while Britten’s is spry and witty.

American Jake Heggie (b. 1961) proves himself to be a worthy heir to his songwriting predecessors. In the first of Gene Sheer’s poems, “Wanda Landowska,” how well does Heggie alternate the bossy, driven attitude of the imperious harpsichordist with her sudden moments of tenderness and sentimentality—for example, the lyrical broadening at the words “There’s so much beautiful music locked away inside.” Heggie also captures Bernac’s bonhomie, Éluard’s single-mindedness, and the passionate nature of the writer and art historian Raymond Linossier. Ainsley varies his tone to accommodate each of these characters, bringing considerable steel to the voice in the poem about Éluard (a stalwart of the French Resistánce during World War Two).

If that weren’t all, the final item in Ainsley’s program is reason enough to buy this CD. Britten’s 1945 cycle The Holy Sonnets of John Donne was completed shortly after Britten had toured Germany with Yehudi Menuhin and had seen at first hand the terrible aftermath of the Nazi death camps. Consequently, this is some of the most emotionally raw music ever produced by a composer better known for keeping his emotions in check. Ainsley throws himself into it, holding nothing back, whether it be in the desperate hectoring of “Batter my heart,” a breathy half-voice to convey private grieving in “O might those sighes and teares return againe,” or the tenderly affecting legato of “Since she whom I loved hath payd her last debt.” Defiance, anger, grief and resolution are all perfectly expressed in this performance, which to my mind is the finest that this cycle has received on record. While the original interpreter Peter Pears (in his 1967 recording with the composer at the piano) is incomparable in such declamatory moments as the opening of “At the round earth’s imagined corners,” overall I find Ainsley more vulnerable—and therefore more human—in this moving work. On the final line of “Death be not proud” (“Death, thou shalt die”), Pears executes a beautifully sustained crescendo, whereas Ainsley invests the line with powerful intensity. The comparison epitomizes their differing approaches.

I have left accompanist Malcolm Martineau to last, but his contribution is crucial to the success of the recital. Throughout, he is in total sympathy with the composers and the singer. In the Donne Sonnets he is more fluent than Britten, and more present than Poulenc in the latter’s 1946 recording of the Éluard cycle with Bernac. As with all Linn recordings the sound quality is first class. The booklet reprints the poems and, where necessary, translations. Everything about this release points to an urgent recommendation.