Florian Boesch - Schumann - Live - The Arts Desk

Florian Boesch is a big man. He’s tall, stocky, and with his bald head and stubble could seem more like a gangster than a Lieder singer. His voice is beautiful, but it matches his appearance – big, weighty and imposing. He has subtlety too, though it is sometimes hard-won, and his affinity with the core Romantic repertoire is always apparent, so this programme, of Schubert, Wolf and Schumann was well chosen to showcase his strengths.

Schubert’s nature-inspired songs are an ideal platform for the more turbulent and dramatic side of Boesch’s temperament. His voice is strongest in the low register, expansive for the stormy vistas of Der Schiffer, but darker and more intense in the forest evocations of Im Walde. He lacks the support required for some of Schubert’s longer lines, or maybe sacrifices it for immediacy and presence.

That was less of an issue in the Wolf songs, six selections from the Mörike-Lieder. Wolf’s style is more aphoristic, and Boesch has a knack for locating the mood of each short number immediately. His colour and delivery here were quite straightforward, his vibrato-less tone offering a conversational immediacy. But it was difficult to gauge his approach to the more devotional songs, Schlafendes Jesuskind and Gebet. Was the simplicity here deliberately naive, or were singer and composer complicit in some subtle irony? The main work in the programme was Schumann’s Liederkreis, a cycle of Eichendorff settings that run the gamut from isolation and despair to idyllic and Romantically transcendental sensuality. Boesch has a tone and a mode of delivery for every mood. Again, the forest evocations, Waldesgespräch and Im Walde, were particularly atmospheric, though more low key and nocturnal than Schubert’s.

In fact, everything in this cycle was more distant and opaque than the more directly expressive settings of Schubert and Wolf, and Boesch relished that extra layer of Romantic abstraction. His tone wasn’t always elegant, and, in the nocturnal settings, Mondnacht and Zwielicht, he often drained the colour from his voice: the menacing last of line of Zwielicht, “Hüte dich, sei wach und munter!” (Be wary, watchful, on your guard!), was literally spoken under his breath. For Boesch, the words always come first, clearly articulated and expressed in his native German.

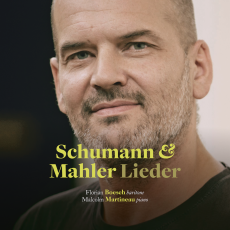

In both recital and recording, Boesch is most often heard with accompanist Malcolm Martineau, who was here in the audience. Justus Zeyen is another regular collaborator, and the two clearly have a natural chemistry onstage. I could imagine more poetry and flow from Martineau in this repertoire, but Zeyen was a competent collaborator. He was a little reticent in the Schumann, allowing the sparse figurations to meander.

The Wolf was more convincing, for Zeyen’s ability to weave together the terse harmonies and maintain colour and focus. But he was at his best in the opening Schubert songs, playing with the expressive abandon of a concerto soloist, rightly confident that Boesch would still be heard. Those tempestuous numbers made an excellent opening to this recital, even if the second half revealed Boesch to be more at home in the intimate, twilit world evoked by Eichendorff and Schumann.